A quick Google Scholar search on disproportionality illustrates the fact that we have a BIG problem in our education system and it’s not new. We’ve been facing the problem of students from diverse backgrounds being over-referred for special education for years.

Here are but a few of the articles you’ll find on disproportionality and over-referral of students from diverse backgrounds from the past two decades:

- 2002: Over-identification of students of color in special education: A critical overview.

- 2006: English language learners struggling to read

- 2009: The disproportionality problem: The overrepresentation of black students in special education and recommendations for reform

- 2012: Culturally different students in special education: Looking backward to move forward

- 2016: Addressing disproportionality in special education using a universal screening approach

What We Can Do to Improve Disproportionality

Let’s take a look at some historical background, reasons that students from diverse backgrounds are over-referred for special education services, and ways we, as speech-language pathologists, school psychologists, diagnosticians, and other educators can help reduce the levels of disproportionality that exist in special education.

Historical Background and Factors that Influence Disproportionality

Artiles and colleagues (2002) reviewed more than 30 years of data and research on the problem of over-identification going back to the 1960s. They noted that at the national level, African Americans, particularly males, are over-represented in Special Education as Intellectually Disabled and Emotionally Disturbed. Latinos and American Indian students are over-represented in other disability categories, such as Learning Disabled and Speech Impaired.

While the needle has moved some, these factors that result in students from diverse backgrounds being over-referred for special education services still persist 20 years later following their work that reviewed 30+ years of data.

As Artiles and colleagues noted,

“The misplacement of students in special education is not only stigmatizing, but it can deny individuals the quality and life enhancing education they deserve.”

A review of the research identifies a number of factors that contribute to disproportionality.

Socioeconomic Factors Contribute to Disproportionality

Poverty, which includes access to pre-natal care, nutritious foods, medical care, secure housing, homes free of lead-based paints, and more, is a contributing factor. Poverty exacerbates the chances of special education placement, but poverty does not account for the disproportionality of representation in special education programs.

Structural and Instructional Factors Increase Chances of Academic Inequality

Funding, resources and quality of schooling play a role. Numerous studies have explored instructional inequalities that stem from inequalities in staffing, teacher salaries, experience of teachers and principals, and conditions of teaching (Darling-Hammond & Post, 2000; Kozol, 1991; Parrish, Matsumoto, & Fowler, 1995; Rothstein, 2000). High poverty schools have a greater percentage of inexperienced and uncertified teachers (Artiles, et. Al, 2002).

Cultural Discontinuity/Referral Bias Results in Students from Diverse Backgrounds being Over-Referred for Special Education

The majority of educators are primarily middle class, female and White. An overwhelming number of special education students are poor, male, and from diverse backgrounds. Teachers make referrals and those referrals are largely based on noncognitive factors, such as speech patterns. Ladner and Hammons (2001) reported that districts with more white teachers had a greater rate of students from diverse backgrounds in special education. Why does this happen? Sometimes when educators see/hear speech patterns different than their own, they view the differences as deficits.

This leads to poor outcomes for those from diverse backgrounds.

“Students identified as English Language Learners [or dual language learners, using strength-based language] have among the highest levels of grade retention and dropout rates of all youth.” Duran, 2008

Assessment Issues That Lead To Disproportionate Representation of Students from Diverse Backgrounds

Traditional assessment models have been found to be inadequate for students from culturally diverse groups (Garcia & Pearson, 1994). There are many reasons for this, including normative samples that do not match the diversity in our schools, culture-specific content of the items, and cultural biases. Many of the standardized tests that are available are Standardized American-English-centric, and language variation results in lower scores. While tests have been improved, these issues still exist.

Vallas (2009) describes further problems with the use of standardized testing tools.

“Despite wide agreement by scholars and scientists that most of the recognized diagnoses are distributed on a continuum, eligibility under the IDEA is determined on a dichotomous basis, using arbitrarily-determined “cutoff points”: either a student is or is not disabled and thus is or is not eligible for services. Indeed, the decision of whether or not a student is placed in a special education program may often be determined by a single point on an IQ or other standardized test.”

So not only do we have problems with the normative samples that are not very representative of our students from diverse backgrounds, we also see that tests that are designed to provide information about a diagnosis with a continuum are used dichotomously with arbitrary cut-off points. For more on the issue of arbitrary cut-off points with standardized tests, see our online course Improve Diagnostic Accuracy by Understanding the Numbers Behind our Tests.

Sometimes examiners mistakenly believe that if a bilingual child is fluent in English, conducting testing in English is sufficient.

I’ve seen this happen way too many in my career. Kids get to the point where they can comfortably communicate in their second language. They get over-referred-for-special-education speech testing because of patterns of native language influence in their English. They are tested in English only and score below average because of their use of native-language influence patterns. Then they are enrolled in special education to receive speech therapy.

Test in both (or all) languages. Even when we don’t have formal measures we can use, we can still use informal measures, such as language samples, to evaluate language skills. We will want to analyze language samples to determine whether or not errors are true errors or simply patterns of influence from the child’s other language.

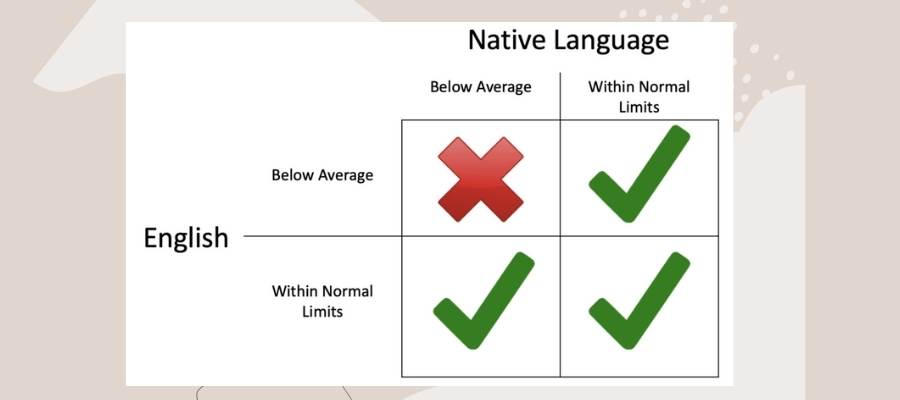

We cannot diagnose a language impairment without exploring both languages of our dual language learners. For those of us working in the schools, this is mandated by IDEA. ASHA summarizes the IDEA requirements nicely. In order for a dual language learner to be diagnosed with a language impairment, they must demonstrate below average skills in both of their languages. As the image below shows, if they are below average in one language and within normal limits in another language, they do NOT have a language impairment, as indicated by the green checkmark. And if we only look at one language, we won’t know if they are below average or within normal limits in the other language. And without knowing that, we have not done a complete assessment and cannot make a diagnosis. See our blog post Best Practices for Testing Bilingual Children for more details on this.

Addressing the Factors that Contribute to Disproportionality

Understand biases and strive to understand differences through a broad lens rather than the narrowly constructed cultural-ethnic standard that has been present in our school systems for so long. Let’s take a look at some of the specific areas we can work to change.

Improve Cultural Responsiveness

Valles (2009) discussed the importance of working to improve diversity in administration and teaching positions. There is a documented widespread shortage of bilingual practitioners (Sullivan, 2011). Further, more rigorous professional development geared toward culturally responsive instruction techniques at the pre-service and in-service levels is needed It can reduce students who are over-referred-for-special-education by catching cultural bias in teachers’ assessment of their students from diverse backgrounds (Valles, 2009).

Value and Learn More About Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

Make information about cultural and linguistic diversity an integral part of undergraduate and graduate programs for all educators. Too often, students have a single course on cultural and linguistic diversity. Diversity exists in every aspect of our lives. It should exist in every aspect of our coursework. We all need to understand that there are differences in cultures, values, knowledge, and communication styles that create the rich world we live in. Celebrate differences and appreciate them.

Work to Build a Strong Understanding of the Patterns of Dual Language Development and Bidialectalism

When people who use two different languages or dialects communicate, they often use rules or patterns from one language in the other. This is a normal process. Our book, Difference or Disorder: Understanding Speech and Language Patterns in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students, is a great resource. We also have online courses that address Speech Patterns and Language Patterns in Diverse Learners.

Evaluate Test Items Qualitatively

After you administer a test to a student, look at their responses to the items. If all of the items they miss are items evaluating to past tense verbs in English, for example, we can see that this could be due to differences in the student’s native language or dialect and English. We can further probe these types of items for more information.

Do Dynamic Assessment

Dynamic assessment or trial therapy allows you to look at learning potential in response to teaching. This reduces testing bias because it avoids the assumption that a student has had experience with what you are testing. Instead, you teach it and look at their learning potential. This sounds like a time consuming process but it really does not have to take a lot of time. Explore our course Practical Dynamic Assessment to learn ways to quickly implement dynamic assessment as a part of your assessment. This is a powerful tool to help you make confident diagnostic decisions. See our blog post Dynamic Assessment: What You Need to Know to get great tips to get you started.

Explore the Use of Code-Meshing or Language Meshing

Home dialects have been undervalued in the school setting. Many children speak language varieties or dialects that are different than the standardized variety of English spoken in schools. Research indicates deficit-based language has been used in the research literature and the classroom when discussing dialectal variation. When students use their home language variety in a school assignment they are often graded lower than those using the standardized variety of English. The cumulative effect of this can lead to referral for special education evaluation.

Language Meshing is an instructional approach that has been proposed as a way to value the languages students bring into the classroom by inviting multiple languages and language varieties within the classroom.

The idea behind this approach is that students who speak other languages and language varieties should be encouraged to share those in the classroom and not be made to feel that their home language or dialect is any less valuable than any other dialect or language. Classrooms that accept only the dominant forms of English as “correct” and “appropriate” can discourage students from diverse backgrounds from participating. Encouraging students to use their home dialects in their classroom conversations and writings shows them that their home dialect is valued. It allows students to reveal and express their perspectives in a personal way. Through the use of code-meshing, teachers are enabled to respect the diversity of the students in their classrooms.

For more on code-meshing, see our blog post on Code-Switching and Code-Mixing—What You Need to Know. Other great resources on this topic include, Mesh It, Y’all: Promoting Code-Meshing Through Writing Center Workshops and Creating Conversation: Code-Meshing as a Rhetorical Choice.

Understand the Problems of Disproportionality and Implement Solutions

Addressing disproportionality means understanding the problems behind why students are over-referred-for-special-education and implementing solutions to address the problems. I’ve seen people try to address the problem of disproportionality without a solid understanding of how to do so effectively. In one rural district we worked with, the special education administration instructed teachers not to refer students with Hispanic surnames for special education. That’s definitely not the right way to solve the problem. Instead, we need to be mindful of the factors that influence the disproportionate representation of students from diverse backgrounds in special education and we need to take steps to address the problems.

I hope that this post have provided some good starting points and I would love to see this community add ideas to it. Let us make a concerted effort to reduce the disproportionality problem that exists in our schools and in our society.

I have included a list of resources below for your reference. It is by no means exhaustive. I encourage you to review them with those in your districts and clinics. Discuss them and think about how you can make changes in your institutions that will have an impact.

- Artiles, A. J., Harry, B., Reschly, D. J., & Chinn, P. C. (2002). Over-identification of students of color in special education: A critical overview. Multicultural perspectives, 4(1), 3-10.

- Barrio, B. L. (2017). Special education policy change: Addressing the disproportionality of English language learners in special education programs in rural communities. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 36(2), 64-72.

- Dever, B. V., Raines, T. C., Dowdy, E., & Hostutler, C. (2016). Addressing disproportionality in special education using a universal screening approach. The Journal of Negro Education, 85(1), 59-71.

- Durán, R. P. (2008). Assessing English-language learners’ achievement. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 292-327.

- Ford, D. Y. (2012). Culturally different students in special education: Looking backward to move forward. Exceptional Children, 78(4), 391-405.

- Fuller, K., & Shaw, M. (2011). Overrepresentation of students of color in special education classes. Journal of Elementary and Secondary Education, 2(7), 1-11.

- Klingner, J., & Artiles, A. J. (2006). English language learners struggling to learn to read: Emergent scholarship on linguistic differences and learning disabilities. Journal of learning disabilities, 39(5), 386-389.

- Sullivan, A. L. (2011). Disproportionality in special education identification and placement of English language learners. Exceptional Children, 77(3), 317-334.

- Vallas, R. (2009). The disproportionality problem: The overrepresentation of Black students in special education and recommendations for reform. Va. J. Soc. Pol’y & L., 17, 181.

Amazing! Very helpful content!

I am a Brazilian SLP and I love to read the articles from you!

Great article. All important factors to consider and certainly these culturally-responsive assessment practices need to be implemented with fidelity on a wider scale within the field. I was lucky enough to have an excellent foundation for fairly evaluating/effectively treating students from diverse cultural-linguistic backgrounds in my grad program. Organizations like Bilinguistics have only improved my skills in this area, and for that I am incredibly grateful.

Before I get into my main point, what do you make of recent reports and studies that indicate under-representation of black males in SPED and “untreated need” amongst students of color? (https://hechingerreport.org/new-studies-challenge-the-claim-that-black-students-are-sent-to-special-ed-too-much/). I worry specifically about under-representation in my school district, which is not to diminish the issue of over-representation.

With that being said, there’s a huge elephant in the room that is rarely addressed in this field (as a primary factor) when it comes to reducing disparities in SPED referrals: the ineffective teaching practices, particularly whole language literacy instruction, that has been adopted widely across the US for decades upon decades.

As experts in language/literacy, SLPs need to push back on this. These practices have led to young, capable minds being left behind, and it disproportionately impacts students of color. I’ve seen it first-hand in the school districts I’ve worked for. These children literally aren’t being taught the skills they need to be successful early on, and it has deleterious effects later on in their development.

Despite this, ineffective instructional practices are often discussed as being THE WAY to increase achievement and close the achievement gap. There is a small but growing movement to change this, led by diverse scholars and educators (see Jasmine Lane: https://jasmineteaches.wordpress.com/2019/12/23/literacy-the-forgotten-social-justice-issue/; https://jasmineteaches.wordpress.com/2019/01/20/why-our-kids-cant-read/), but it’s being drowned out after the events of this past summer, as in-vogue yet ineffective instructional practices are amplified once again.

We know what works for students, including at-risk students, students from low-SES backgrounds, and multilingual students when it comes to teaching literacy and a whole host of other subjects (see: Project Follow Through 1977, National Reading Panel 2000, Rose Report 2006). The research is well-established. Yet it’s been ignored, pushed aside, or simply not taught in undergraduate/graduate education schools, mainly by radically “progressive” educators, professors, and policy wonks. This has to stop. We have to talk about it more.

But, as mentioned above, since last summer, it’s becoming increasingly more difficult to have conversations about best instructional practices, especially when these practices are in direct conflict with what radical educational advocates propose, namely: less direct instruction, less or no explicit/systematic phonics instruction, more “balanced” literacy, more student-led/inquiry-based learning, etc. We could have the same debate for math instruction.

Implementing EBP instructional practices is not in conflict with creating culturally-responsive classrooms/therapeutic settings, yet it’s becoming a dichotomous debate. Recently, some attempts to push-back on these bad teaching methods result in being called “racist”, “complicit”, or a “colonizer”, social ostracization, and/or employment concerns. For me, I don’t care. For others, they retreat and do what they know is best on an individual level, but they definitely don’t advocate for what change is needed in the public-sphere or at the organizational level.

In my area, it’s not due to lack of funding. Districts, including urban, are incredibly well-funded. Teachers/therapists are paid well, benefits are good. Yet the school systems are wrought with fad teaching practices that don’t help students on the whole. Rather than looking inward, systemic racism is blamed as the sole factor for underachievement, goalposts with regards to student outcomes are shifted, too many students of color are referred to SPED (or in some cases, not referred enough), and ineffective teaching practices live on or are replaced by equally ineffective practices. Attempts for meaningful change are resisted by other educators/therapists, educational administration, and often the state union.

How do we talk about this? What do we do?

Hi Rachel,

Your comment shared how incredibly complex all of this is. It IS difficult to have these conversations and it IS uncomfortable but it is also necessary (as you also shared). I can share two ways we are approaching the problems you highlighted with some success. Albeit, this topic is still difficult.

We need to move away from the words over-identification, under-represented, and disproportionate when talking about special education. I think that these words immediately put districts back on their heels and make SLPs feel like they aren’t being culturally sensitive or doing their jobs. We have had more success reducing caseloads and getting the right students in by talking about “proportionality/proportionate representation. This includes everyone and doesn’t point fingers. As an example, let’s say you have a school with 1000 kids. The make-up is 500 white, 250 black, and 250 Hispanic-surnamed. Knowing that special ed should be around 8-10%, that would be 50/25/25 (ish).

What this does is shines a light on over- and under-representation. It shines a spotlight on problematic policies and representation.

The second thing we have been doing is talking about Reducing Our Caseload within the above framework. SLPs are 1) SUPER busy and 2) feeling disempowered with trying to figure out how to make change. If each of us focuses on the kids we can move off, we can make space for the kids to move on.

The third thing that we can do is use literacy-based intervention. We can’t fix or really influence the literacy rates at large but literacy-based intervention accounts for experience, culture, and second-language influence. Too much to highlight here but you watch a video and here about a course we put together here: Literacy Based Intervention

Implementing EBP instructional practices is not in conflict with creating culturally-responsive classrooms/therapeutic settings,