We know that Code-Switching and Code-Mixing are TYPICAL processes for those who speak more than one language or more than one dialect. They are powerful strategies that require metalinguistic skills and are NOT indicative of language impairment. Often, speakers who use two languages together are described as “confused” or “they don’t know either language well.” That simply isn’t the case. Let’s take a look at the research.

Let’s Start with the Definitions

Code-Switching

Alternating between two or more languages or language varieties/dialects in the context of a single conversation. Using elements of more than one language when conversing in a manner that is consistent with the syntax, morphology, and phonology of each language or dialect.

Code-Mixing

Truth be told, many people use the terms Code-Switching and Code-Mixing interchangeably. Some linguists, however, make a distinction in which Code Mixing refers to the hybridization of two languages (e.g. parkear, which uses an English root word and Spanish morphology) and Code-Switching refers to the movement from one language to another.

Many pairs of languages have a hybrid name. Some languages hybridized with English include Spanglish for Spanish, Hindlish for Hindi, and Frenglish for French.

Code-Meshing

Code meshing is an instructional approach that invites multiple languages and language varieties within the classroom.

The idea behind this approach is that students who speak other languages and language varieties should be encouraged to share those in the classroom and not be made to feel that their home language or dialect is any less valuable than any other dialect or language. Classrooms that accept only the dominant forms of English as “correct” and “appropriate” can discourage students from diverse backgrounds from participating. Dr. Brandy Gatlin-Nash introduced us to the term Code-Meshing at the Bilinguistics-SLP Impact Virtual Conference on Building Equity for Diverse Learners in Special Education. She discussed the importance of encouraging students to use their home dialects in their classroom writings and then using the students’ work to teach them to be bidialectal. It allows students to reveal and express their perspectives in a personal way. Through the use of code-meshing, teachers are enabled to respect the diversity of the students in their classrooms.

What is an example of code mixing?

For more on code-meshing, see Mesh It, Y’all: Promoting Code-Meshing Through Writing Center Workshops and Creating Conversation: Code-Meshing as a Rhetorical Choice.

Translanguaging

Translanguaging is is another term occasional used to describe the use of two languages.

A few years ago I was asked by a school district SLP what the deal is with this new term “translanguaging.” She said, “I just don’t see how this is any different than code-switching and code-mixing.”

So, what exactly is translanguaging? Well, when a child uses translanguaging, he or she uses any and all of his language knowledge, structures, etcetera, to communicate. So when we use a dual-language approach in our assessments, we are allowing for translanguaging. Or, more easily stated, we let kids use both (or all) of their languages/language varieties to accomplish tasks.

I read a blog post by Francois Grosjean, (you know, the guy who shared with us in the 80s that a bilingual is not two monolinguals in one), who says that translanguaging is the same behavior as “interacting with other bilinguals, changing language base freely, translating whenever needed, and intermingling one’s languages in the form of codeswitching and borrowing.” He interviewed one of the term’s most visible proponents, Ofelia Garcia, and asked her what the difference is, and what the benefit is in replacing the terms. She stated that it may look the same from the outside but the difference is that those earlier terms are an external views of language while “translanguaging takes the internal perspective of speakers whose own mental grammar has been developed in social interaction with others.” In a nutshell, it is allowing the use of any language content and construction for expression.

Why do people use Code-Switching, Code-Mixing, and Code-Meshing?

There are many reasons that people who are exposed to more than one language or language variety use code-switching and code-mixing.

Sometimes Ideas are Better Expressed in One Language than Another

Sometimes ideas are better expressed in one language than another for people. This can be due to having the vocabulary in one language but not the other. It can also be that the idea is culturally bound. An example that a friend who spent a lot of time in Bolivia shared was pay de manzana, which translates literally to apple pie but pay de manzana in Bolivia was very different for her than apple pie in New York, so when she was describing her Bolivian experience, she used pay de manzana.

This connection between culture and food is also illustrated in research studies. Peña and colleagues (2002) asked elementary school students to name all of the foods they could think of. They asked students the same question in different languages on different days. What was so cool about this study is that the students gave roughly the same number of items when asked in Spanish and English but they didn’t give the SAME items. In English, the top items included hamburgers, hot dogs, and French fries. In Spanish some of the top items included tacos, frijoles (beans) and caldo (soup). This shows how closely tied together language and culture are. It’s not just a different set of words for saying the same thing, it’s a different mode used in different situations.

Languages and Dialects Are Used to Mark Ethnic and Group boundaries

Hall and Nilep (2015) describe the impact of code-switching on ethnic identity.

“Code-switching [is] a product of local speech community identities. Speakers are seen as shifting between ingroup and outgroup language varieties to establish conversational footings informed by the contrast of local vs. non-local relationships and settings.”

Connecting with your people

One of my favorite code-switching features is the “lah” used in Malaysian and Singaporean varieties of English (or Manglish and Singlish, as they are known). These two countries share a long history and the linguistic particle “lah” is something they have maintained despite Singapore’s independence from Malaysia in 1965. The term “lah” can be used to express affirmation, dismissal, exasperation or exclamation in different contexts. But you can’t just stick the word “lah” any old place in a sentence. Those from Singapore and Malaysia cannot always explain what the appropriate use of “lah” is but they can always tell when you don’t use it correctly! Here’s a great article on this if you’re interested in reading more.

Marking in-group (informal) vs out-group (more formal)

The way we speak also has the power to make us feel close to people or in a more formal relationship. This has been well documented. As far back as the early 80’s Genesee (1982) and Bourhis (1983; 1984) studied people’s reactions to different types of code-switching and found that the groups in their studies (English speakers and French Canadian speakers) consistently expressed favoritism toward ingroup language choices.

And there are many other reasons people use code-switching and code-mixing.

These include quoting other people, clarifying or explaining a point a point, adding personality to a comment, emphasizing a point, reflecting your mood, and so on.

What is an example of code switching?

First, we should note that there are rules to code-switching. Segments in each language or dialect follow the rules of that language or dialect. There are also rules about where in an utterance code switching can occur (such as phrase boundaries). These rules vary somewhat by language because they are guided by the languages used in code-switching. We’ve included links and references to some great resources at the end of this post so you can explore your languages of interest.

Below are some examples of code-switching from evaluations I have done of students who were not diagnosed with a language disorder.

Single Word Code-Switching

Here’s an example of single word code-switching from a 6-year-old Spanish speaker who has been in the process of learning English for 2-3 years. Single word code-switching can be done for specificity in vocabulary or when a child does not know a label in both languages.

The venado (deer) run and he go off a cliff.

Phrasal and Intersentential Code-Switching

The following is the Capi Story from the PLS-5-Spanish told by a child who was 4;6 and has grown up speaking both languages at home. He is in a dual language classroom for pre-Kindergarten. Notice that he switches from one sentence to another, sometimes from one phrase to another, and in dialogue.

- Capi was dormido aquí. (Capi was asleep here)

- The girl say, “¿Qué podemos hacer?” to the boy. (The girl say, “What can we do?” to the boy)

- Hacen una casa. (They make a house)

- He was making the house and he cut out a door.

- Y él tiene su cobija y está happy. (And he had his blanket and he was happy).

Code-switching in dialogue

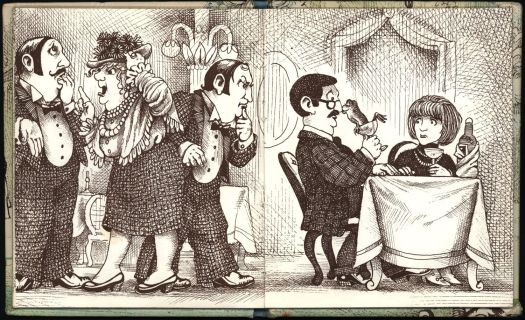

Next is a brilliant example of code-switching by a 6-year-old girl who speaks Standardized American English dialect and African American English dialect. The excerpts are from her retelling of the Mercer Mayer wordless picture book Frog Goes to Dinner.

She used Standardized American English dialect for the parents when they were ordering food in a restaurant and African American English dialect for the parents when they were disciplining their son at home. If that doesn’t show you that she grasps the use of the two dialects, I don’t know what does. Here’s to 6-year-old metalinguistic skills! (Contextual information is in parentheses following each utterance.)

- The boy is looking at the mirror. (He is getting ready to go out to dinner with his parents)

- The dog was sad and the boy was leaving.

- I will have a drink of wine. (The parents talking to each other at the restaurant)

- Waiter, we will have a cup of wine and spaghetti. (The parents ordering from the waiter)

- (Then the boy’s frog gets out and wreaks havoc at the restaurant.

- Please, that’s my frog. (The boy says to the waiter).

- (The family then gets kicked out of the restaurant)

- You gonna be grounded six days! (Parents talking to son at home: AAE use of the Zero Copula)

For more information check out: Why Understanding Cultural Parameters is Important to SLPs

How do we write about Code-Switching and Code-Mixing in Speech-Language Reports?

I know I don’t need to say this again but I’m going to anyway. Code-switching and code-mixing not indicative of language disorder. That’s not to say that a child who code-switches can’t have a language disorder but it not INDICATIVE of a disorder. So how do we talk about this is our speech-language evaluation reports?

Here are a couple of examples I pulled from reports I have written.

He was noted to code-switch, often using a Spanish word in English when he did not appear to know the name of it in English. Code-switching is a normal process in children acquiring two languages.

With the examiner, he used Spanish more easily than English, but demonstrated an increasing English vocabulary as he often used English words within Spanish utterances. This phenomenon of using more than one language within or between utterances, known as code-switching, is common for both bilingual children and adults. It shows flexibility of language skills and that Student is able to access both systems as needed to most effectively communicate a message.

So there you have it. Code-switching is a normal process used for a wide range of reasons by children and adults who are exposed to more than one language variety or dialect. It doesn’t equate to confusion, and in fact indicates strength in metalinguistic skills. And don’t you forget it, lah.

References

- Bland-Stewart, L. M. (2005). Difference or deficit in speakers of African American English? What every clinician should know… and do. The ASHA Leader, 10(6), 6-31.

- Bourhis, R. Y. (1983). Language attitudes and self‐reports of French‐English language usage in Quebec. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 4(2-3), 163-179.

- Bourhis, R. Y. (1984). Cross-cultural communication in Montreal: Two field studies since Bill 101. international Journal of the Sociology of Language, 1984(46), 33-48.

- Genesee, F. (1982). The social psychological significance of code switching in cross-cultural communication. Journal of language and social psychology, 1(1), 1-27.

- Hall, K., & Nilep, C. (2015). 28 Code-Switching, Identity, and Globalization. Discourse Analysis, 597.

- Peña, E. D. (2012). Code-Switching Doesn’t Mean Confusion. 2 Languages 2 Worlds Blog.

- Peña, E. D., Bedore, L. M., & Zlatic-Giunta, R. (2002). Category-generation performance of bilingual children.

- Seymour, H. N., Bland-Stewart, L., & Green, L. J. (1998). Difference versus deficit in child African American English. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 29(2), 96-108.

- Bland-Steward, L. M. Difference or Deficit in Speakers of African American English? What Every Clinician Should Know. https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.FTR1.10062005.6