I have been involved in a recent research project to document how to effectively account for the influences of African American English Dialect during speech language therapy This work is critical on a global level so that speech language pathology is in lock-step with other professions bringing equity and voice to all the populations we work with. This work is also critical on a professional level for me and anyone working with diverse populations.

As a non-Black clinician, I tuned in to presentations, research, resources, and work of Black clinicians. Their work deeply influenced how I now serve diverse students and introduced me to many of the things we need to consider when thinking about African American English Dialect and speech language therapy. Find out more about these amazing colleagues of ours and the work they do:

Celebrating our Black SLP Colleagues,

Authors, Books, and Resources to Promote Diversity and Inclusion

Here, I would like to summarize information on African American English Dialect so that we can be informed when choosing goals and deciding what to work on in speech therapy. Learning, revisiting, and putting into practice this information is part of our work as educators and therapists.

In grad school and throughout my career, I knew the basics – AAE is a dialect, and dialect use should not be confused with a speech or language disorder. In other words, dialect does not equal disorder, and our evaluations should reflect that.

However, I continue to inherit students on my caseload with goals to use features of Standardized American English (SAE) in their speech, although they are speakers of AAE. I continue to receive referrals from teachers requesting speech and language evaluations for students who are speakers of AAE because of speech sound and grammatical differences that are a part of their dialect. These situations continue to happen for many, if not all, clinicians and can be improved by learning about AAE’s rich history and understanding how to evaluate our current goals to make sure that they focus on communication disorders and not aspects of dialect.

African-American Students in Special Education

African-American students have historically been over-represented in special education. In 2018-2019, African-American students enrolled in elementary and secondary public school accounted for 15 percent (7.7 million) of the general population, and they accounted for 16 percent of the special education population.

Many of these children enter special education with a diagnosis of speech and/or language disorder. In order to accurately diagnose speech and language disorders, an understanding of dialectical influences on language is critical. Just as we consider the language differences of children whose first language is other than English, we should consider the language differences of children whose dialect is other than “standard.” The research supports that “there is a marked increase in the use of African-American English (AAE) features between the ages of three and five” (Bland-Stewart, 2005), which coincides with most children’s entry into the U.S. Education System. “Dialect shifting to Mainstream American English (MAE) appears to emerge between Kindergarten and 2nd grade” (Craig & Washington, 2004). The majority of students diagnosed with speech and language disorders in the school setting are likely to be identified between the ages of three and nine, or between preschool and third grade.

As school-based clinicians, we must be aware of these dialectal differences, and must take them into consideration before diagnosing a disorder, and beginning the path of special education, which can alter a student’s educational trajectory. Simply put, African American English (AAE) dialect has different rules than SAE.

It is a dialect that has deep historical roots, and is “a grammatical system that is as systematic as that of SAE. It is not a substandard, uneducated, or lazy way of speaking.”

PBS curriculum (2005), Do You Speak American?)

A Short History of African American English

The history of AAE stems back to individuals of different language backgrounds being transported from Africa to America as slaves, who developed a simplified version of language (a pidgin) in order to communicate between the groups that did not have a common language. This language subsequently developed into a full-fledged creole language that children acquired in their homes. Another theory is that slaves in the South worked alongside indentured servants who spoke non-mainstream varieties of English. African American slaves learned English from these indentured servants (often of Scottish-Irish descent). People who believe this explanation for the beginning of AAE say that it explains similarities between AAE and other non-mainstream varieties of English (such as Appalachian English, which shares some linguistic features with AAE). However AAE was developed, it has systematic grammatical rules, and it carries important social functions.

AAE has survived post-slavery because it became more than just a means of communicating between groups; it is a source of solidarity among the speakers of this dialect and an important part of African American Culture.

Identifying Appropriate Speech Goals for Students Who Use AAE

In 2018, I began services mid-year for a caseload of high-schoolers, 90% of whom were Black and used at least some features of AAE. As a bilingual (English-Spanish) clinician, I was tuned in to differentiate difference from disorder, but this was one of my first opportunities working with a predominately Black caseload. Here are a few highlights of the goals that were on students’ IEPs, at varying levels of complexity:

- Mark 3rd person singular -s

- Mark plural -s

- Mark regular and irregular past tense verbs

- Produce voiced and voiceless “th”

- Produce clusters in all positions of words

- Include copula and auxiliary verbs in sentences

- Produce subject, object, and possessive pronouns correctly in sentences

- Produce grammatical sentences to respond to questions/produce a narrative

At first glance, these all seem like “reasonable” IEP goals. And they can be For speakers of Standard American English (SAE). I put on my “difference or disorder” hat and started to pick these goals apart, and found that so many of the goals on my students’ IEPs were inappropriate given their dialect.

Examples of AAE Rules and Speech Therapy Goals

| Goal: | AAE Rule(s): | Example: |

| Mark 3rd person singular -s | 3rd person singular -s may be omitted or it may be used with the 1st person. 3rd person singular -s may mark both a main verb and an infinitive in the same sentence | The boy want to run./ The boy wants to run.I does./ I do.She want to eats it./ She wants to eat it. |

| Mark plural -s | Plural -s is omitted to reduce redundancy with nouns of measure (i.e., numbers) Final consonant reduction for plurals containing clusters Regularization may occur by adding plural –s to irregular plurals | He have fifty cent./ He has fifty cents.Here two shoe./ Here are two shoes.They have three childs./ They have three children.Tesses/Tests |

| Produce regular and irregular past tense verbs | Past tense marker final “-ed” is not required. Ongoing past events are indicated with “been” Past participle may be used in place of irregular past tense. Overregularization- Regular past tense marker “-ed” may be used in place of irregular past tense | He start crying an hour ago./ He started crying an hour ago.She been done./ She finished work (a long time ago).They been had that dog./ They had the dog (for years).She seen him./ She saw him. He knowed it./ He knew it. |

| Produce voiced and voiceless “th” | Replacement of voiceless “th” (/θ/) with /f/ in medial and final positions Replacement of voiced “th”(/ð/) with /d/ in the initial position Replacement of voiced “th” (/ð/) with /v/ in the medial position | birthday /bɝθdeɪ/→ [bɝfdeɪ] south /saʊθ/→ [saʊf] them /ðɛm/ → [dɛm] brother /brʌðɚ/ → [brʌvɚ] |

| Produce consonant clusters in all positions of words | Reduction of final consonant clusters in singular nouns Reduction of final consonant clusters in plural nouns | test /tɛst/→ [tɛs] hand /hænd/ → [hæn] tests /tɛsts/→ [tɛsəs] wasps /wɑsps/→ [wɑsəs] |

| Include copula and auxiliary verbs in sentences | “Zero copula” is a systematic rule. The copula is deleted when it is contractible and not required, yet included when uncontractible and obligatory for the meaning or intention of the sentence. May use “was” instead of “were” in past tense Auxiliary verbs are invariably included as determined by context and contractibility. Auxiliary verbs are not required in present progressive sentences | They angry./They are angry. She a doctor./She is a doctor. We was scared./We were scared. He eatin.’/ He is eating.He talkin.’/He is talking. She got homework./She’s got homework. |

| Produce correct subject, object, and possessive pronouns in sentences | Subject or object pronouns may be used to denote possession. Undifferentiated pronoun case. Subject, object and possessive pronouns may be used more interchangeably than SAE. Regularized reflexive pronouns; may include “heself” “hisself” “theyself” 2nd person plural pronoun “y’all” is used Demonstrative pronouns- use of “them” in place of “these” or “those” | I need them books./I need those books.That they laundry./ That is their laundry.Her go to the store./She goes to the store. He wash he self*/He washes himself. Where y’all goin?/Where are you all going? |

Generic “catch-all” Speech Goals

As you see in the chart above, there are a number of grammatical differences and variations between AAE and SAE. Generic “catch all” goals such as; “Produce grammatical sentences to respond to questions” or “Use grammatical sentences 80% of the time while retelling a story” are not only is not specific enough for an IEP or a treatment plan. They are also inappropriate for a speaker of a dialect different from SAE, or who is a second language learner. Sure, a clinician could denote “Produce grammatical sentences using SAE or AAE dialect 80% of the time while telling a story,” or some variation of that, but the measurability simply is not there due to so many potential dialectal influences.

A few other differences of AAE vs SAE that would affect the “grammaticality” of sentences in such a goal include:

| Rules of AAE Dialect | Example |

| Prepositions are variably included. They may be omitted, added, or distributed differently than SAE depending on context. | Get out the car./Get out of the car. |

| Allows for double comparatives- more or most plus the morpheme -er or -est in the same sentence. | That flower is the most prettiest./That flower is the prettiest. |

| “An” is substituted with “a” before nouns, regardless of vowel context. | I want a apple./ I want an apple. |

| Possessive ‘s is not required when possession is already indicated, OR possessive ‘s may be added to possessive pronouns. | That John ball./ That is John’s ball. |

| “Be” is used to indicate a habitual, ongoing action. “Be” may be inflected. | I see she be biking (everyday)./I see her biking everyday. |

As highschoolers, some of whom had been receiving speech therapy and special education for most of their school years, my students were disgruntled to say the least. They were over coming to speech therapy, and sometimes could be downright rude. I couldn’t blame them. The way I connected best with them, was by being honest and explaining the process to them. We talked about the differences between dialects, I let them openly share how/if their speech and language prevented them from talking with their peers, teachers, or family. We shifted their goals to help them feel more confident with communicating their thoughts and feelings, taking the focus off of “grammaticality” and speech sounds attributed to dialectal differences. And for many, I told them I was there to help them finally “graduate” from speech therapy. It became my mission to educate the students, teachers, and parents on “difference vs disorder,” and to get some of these students off of the speech caseload. It helped my students have greater buy-in, and it definitely changed their respect and willingness to talk with me. It took a lot of work, but I got many of them re-evaluated and dismissed from speech therapy. That was my proudest accomplishment of that school year.

The last point I want to leave you with is this:

“Not all African Americans speak AAE, and not all speakers of AAE are African Americans. Some African Americans may speak Mainstream (Standard) American English, and some non-African Americans may use AAE features in their speech.”

PBS, 2005 Do You Speak American?)

Dialect is so nuanced. Parental/caregiver interview is such a crucial step before delving into an evaluation and making important diagnostic decisions that can last the span of an individual’s life. We must know where our students come from, what the language or dialect of that region is, and pay close attention to the parents’ use of language and dialectal features.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. Please, let my experience encourage you to take a look at your caseload with a different lens.

Alyson Hendry of Speech and Movement in Louisville, Kentucky, writes about African American English Dialect in Speech Language Therapy and her experiences serving Black students in the schools. Alyson worked at Bilinguistics for 6 years, leading our school services division until 2015 when she set off on an adventure as a traveling therapist. We continue to collaborate with her on many fronts.

Thank you!

Excellent blog. I was recently in a debate with a friend sharing this type of information. I now have a resource to share. Thank you!

Glad too hear it. We have an article coming out soon on applying the Difference or Disorder framework to AAE too. Be on the look out for that. Also, here are two more articles in this series: https://bilinguistics.com/resources-for-diverse-caseloads/ https://bilinguistics.com/promote-diversity-and-inclusion/

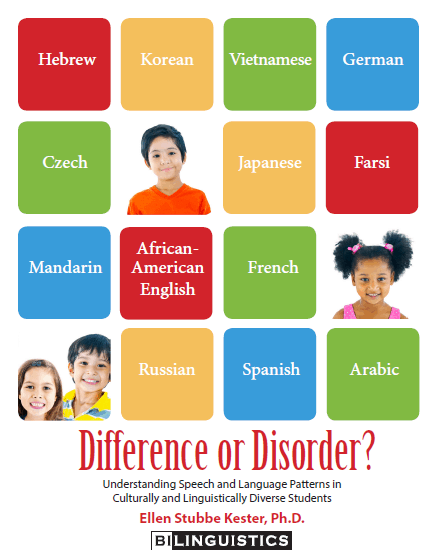

And our Difference or Disorder Book has a chapter on AAE: https://bilinguistics.com/catalog/products/difference-vs-disorder-understanding-speech-and-language-patterns/

Awesome article, thank you 🙂

Glad you enjoyed it. This is one of four articles we are writing on AAE and contributions of Black SLPs to our field. Be sure to check those out too.

Great article! Very informative. Do you have some examples of what to say to teachers and parents to help them understand difference vs disorder?

HI,

So I need some advice. If children do use AAE, do we still expose them to SAE but just don’t make goals to reflect that? I’m in a school setting and I usually say that we sometimes talk differently depending on who we are around. I then call SAE “school talk”. Is this inappropriate to do? I usually bring up my strong Philadelphian dialect and say that is how I talk when with my friends and family.

Please help. I don’t want to offend anyone.

Thanks