Have you ever thought about how unbalanced our understanding of language disorders is compared to speech sound disorders? On the language side we are really comfortable with some very technical words like morphology, syntax, and pragmatic use. But what has speech sound disorders research given us? We have articulation and phonology. Going past that, maybe we can head into completely different camps that affect speech like VPI, hearing, and stuttering. But, our treatment of typical unintelligibility is kind of limited.

Speech vs. Language

| Speech | Language |

|---|---|

| Articulation | Receptive |

| Phonology | Expressive |

| ? | Syntax |

| ? | Pragmatics |

| ? | Morphology |

| ? | Semantics |

Shouldn’t we have a better description of the many different ways a child is unintelligible? And if we can get there, shouldn’t there be different ways to treat those areas? I mean, you wouldn’t do semantic therapy with a child who has grammar goals. And you wouldn’t focus on pragmatic language for a child who produces small utterances. But how many speech pathologists mix-and-match articulation and phonological approaches? How many of us have a solid understanding of when a child is unintelligible due to difficulty being consistent versus not being able to follow a rule, versus not being able to say a sound?

What we need is a better way to help a child by knowing HOW they are being unintelligible, and what we should do about it in speech therapy.

Here is a bit of research on three groups who have worked to better define speech sound disorders. The last one is my favorite and I will share why I think it is the most applicable to the work setting.

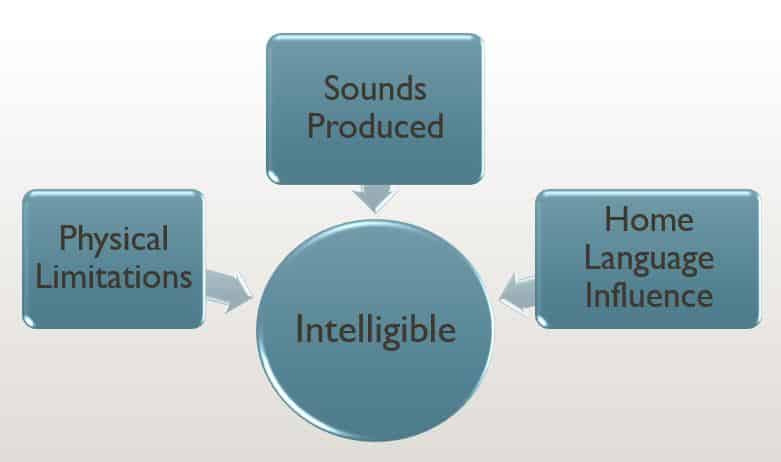

Defining Intelligibility

At its foundation, low intelligibility is the result of a small number of reasons. In each case that we can’t understand a child to some degree, it is due to:

- A physical limitation – E.g., a cleft palate, hearing

- Sounds that can’t be produced because of placement – E.g., articulation

- Sounds that are not produced at the right time because a rule is being broken – E.g., phonology

- A primary language is negatively influencing the sounds a child is trying to produce – E.g., home language influence

It goes without saying that children who fall into the different groups above probably need different interventions to become more intelligible. And if we could decide on better descriptiveness as a field, then we could could align goals, therapy, and research to get faster results.

Subgrouping children into clinically validated subtypes of SSD allows for more precision in the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of these disorders. However, to date, there is no single classification system of SSD that is employed uniformly by SLPs (speech-language pathologists).

Lewis, et al 2012 Subtyping Children With Speech Sound Disorders by Endophenotypes

Speech Sound Disorders Research Models for Defining Intelligibility

There are broadly three primary ways speech sound disorders research has tried to better define low intelligibility. They are grouped based on the cause of the disorder, they are described based on how they are affecting educational outcomes like reading, and they are divided into subclasses based on the type of error that is produced. Let’s review each here and link out to the authors and researchers.

Seven Subtypes of SSD

Lawrence Shriberg has done an insane amount of research on sound disorders. If you are not familiar with his name, know that a lot of his work has influenced what we all covered in grad school. I included six of his studies in the references in the end. I will do my best to sum up some of his ideas on subtyping SSD (Dr. Shriberg, if you are reading this, my apologies in advance!).

Speech sound disorders can be described based on their cause. These are described as the following classes:

- Genetic

- Otitis Media

- Apraxia

- Dysarthria

- Psychosocial Involvement

- 2 groups based on errors

This type of research make you feel good because we all love to know the cause of an issue. The difficulty that I have as a therapist is that the intake information that I have does not always provide enough information as to the cause, the family might not know the cause, and there aren’t interventions aligned with all of the causes. What do I do in the case of a genetic mutation? Do I intervene differently with Apraxia versus Dysarthria? Shriberg does talk about two groups based on errors, which falls under articulation and phonology, so that helps.

Overall, while cause or etiology might be the most accurate way to describe a speech sound disorder, it doesn’t provide me with the clearest path forward with intervention.

Psycholinguistic Model

Who doesn’t like a big juicy word like “psycholinguistic?” Stackhouse and Wells’ 1997 book Children’s Speech and Literacy Difficulties: Identification and Intervention: Book II is a cornerstone for speech programs in most English-speaking countries. They tie speech problems to academic problems and show the direct correlation between literacy rates of children who have trouble producing sounds and their intelligibility.

Now we are getting somewhere. This is easy to understand and I see how my role ties to the curriculum and education system. I am a firm believer in tackling literacy and communication together and included many of these ideas in Literacy-Based Intervention.

However, if I am allowed an opinion, it’s this: Our time in clinics is almost devoid of information on school progress. Our time in the schools is so limited that it is very difficult to tackle academic and speech goals simultaneously. While we can incorporate literacy into our therapy (and should!), it’s hard to monitor the child’s literacy rates at the same time we are monitoring intelligibility.

So while I can’t disagree with anything they say, and while I thank them for what they have contributed to the field, I was still left wanting more for my students and clients that really struggle with intelligibility.

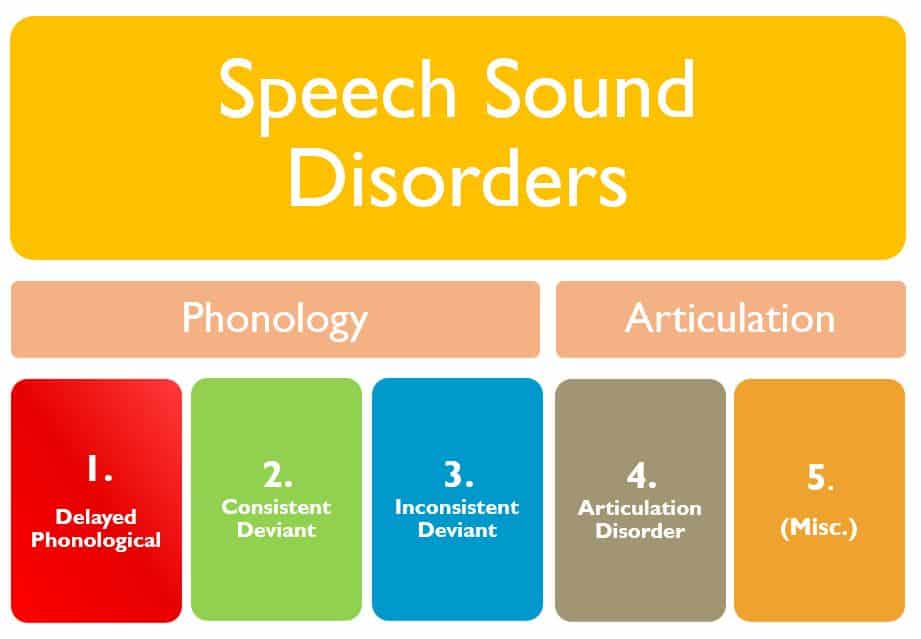

Behavioral Appraisal of Speech Sound Disorders

In 2005, Barbara Dodd published work on how to 1) differentially diagnose and 2) treat speech sound disorders. I don’t want the importance of their goal to be lost so let’s break it down. Right out of the gate they are looking for what separates one issue from another, and then try to figure out what to do about it.

This speech sound disorders research is laid out like our extensive knowledge about language disorders. We have very specific “behaviors” or ways sounds are being said in error, and therefore we should have very specific ways to treat them. The research suggests that phonology should be better described into three groups:

Delayed Phonological: Phonological system similar to younger, typically developing children.

Consistent Deviant Phonological Disorder: Errors that are consistent patterns, but SHOULD NOT be seen by any child at any age. E.g, deleting all syllable-initial consonants.

Inconsistent Deviant Phonological Disorder: Variable productions of the same words or phonological features in the same contexts and across contexts.

This was new information for me when I first read it. I was familiar with delayed phonology of course but had not thought about phonology that should not exist (consistent deviant) or phonology that broke the consistent rule patterns (inconsistent deviant).

These following two groups were more familiar to me and more obviously needed different treatment approaches.

Articulation: An inability to produce a perceptually acceptable version of particular phonemes, either in isolation or in any phonetic context.

Miscellaneous: Low intelligibility attributed to physiological factors such as hearing impairment or craneo-facial anomalies.

We created two charts to help identify what you should be focusing on, which you can find here: Correctly Matching Speech Sound Disorders to Appropriate Therapy

We also made a 90 minute ASHA CEU course with video examples of each of the subtypes and therapy examples for how to apply the research: Success with Speech Sound Disorders

References:

- Dodd B. Differential diagnosis and treatment of children with speech disorder. 2nd. Philadelphia: Whurr; 2005.

- Shriberg LD, Kwiatkowski J. Phonological disorders III: A procedure for assessing severity of involvement. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1982;47:256–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Kwiatkowski J. A follow-up study of children with phonologic disorders of unknown origin. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1988;53:144–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Kwiatkowski J. Developmental phonological disorders I: A clinical profile. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:1100–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Kwiatkowski J, Best S, Hengst J, Terselic-Weber B. Characteristics of children with phonologic disorders of unknown origin. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1986;51:140–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Lewis BA, Tomblin JB, McSweeny JL, Karlsson HB, Scheer AR. Toward diagnostic and phenotype markers for genetically transmitted speech delay. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:834–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Tomblin JB, McSweeny JL. Prevalence of speech delay in 6-year-old children and comorbidity with language impairment. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 1999;42:1461–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackhouse J, Wells B. Children’s speech and literacy difficulties. London: Whurr; 1997.

Whatever happened to phonological processes analysis.?

Yes! What I think this research does better than what we have in the past is that it dives one level deeper than phonological process analysis. Dodd’s work actually better defines it as three separate groups. So not only do you get an idea of the processes that are being used or creating errors, but specific ways to treat them. Check out the CEU course above because it’s 90 minutes of discussing this very topic.

I updated the links to this blog post and added more resources due to so many of your responses. Thank you for the suggestions.

On your chart, where would CAS fall?

CAS is actually not part of this chart because in the research it is considered separately because of its uniqueness like fluency and hearing loss influenced speech issues. Highly unintelligible, inconsistent phonology issues are often confused with CAS. However with CAS the syllable sizes are tiny while phonology is highly unintelligible but utterance length is not affected. Here is some Apraxia-specific information: (Childhood) Apraxia Causes, Characteristics, and Resources 5 Tips for Working with Childhood Apraxia of Speech