How Phonology in Bilingualism Contributes to Over Identification: A Case Study

We have all seen comparisons of Spanish to English that help us work with children across languages. But what do we focus on in our English-only therapy with children who speak Spanish in other contexts, such as with friends or at home?

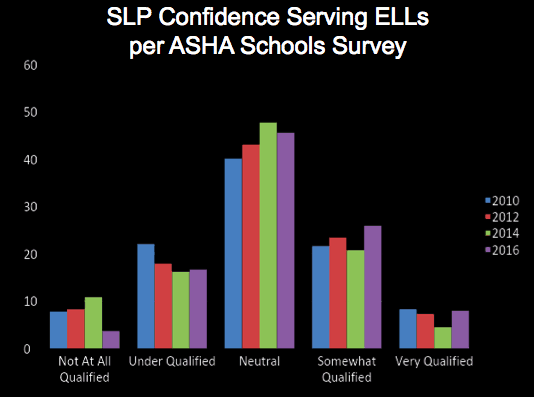

Disproportionality, over-representation, and over-identification of bilingual speech students are all terms highlighting the fact that the proportion of English language learners in special education is higher than in general education. As professionals, we want to do best for these kids but part of the problem is that we don’t always have the tools and information we need to make confident decisions about who we serve.

A small number of studies (referenced below) have been conducted on phonological skills in bilingualism, but the results vary widely because of the different languages they studied, different ages of the children, and different levels of bilingualism.

Here is what we wanted to know about over-identification of bilingual speech students.

Do the patterns of phonological processes in English differ for monolinguals and Spanish-English bilingual children?

And, how do we use this information to confidently make diagnostic and treatment decisions?

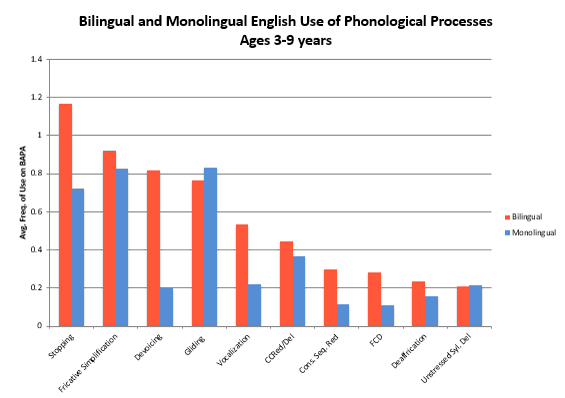

We tested 322 students between ages 3 and 9 years using the Bilingual Articulation and Phonology Test, which tests all phonemes in each position, multiple times. There were 143 monolingual children in our study and 179 bilingual children.

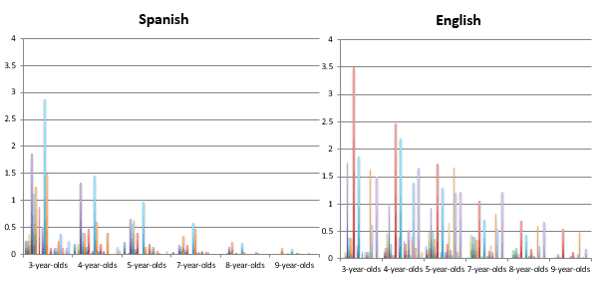

Here is what we found. Just like with monolingual speakers, use of phonological processes diminishes over time. The y-axis shows the average number of times the phonological processes were used on the BAPA by bilingual children in Spanish (left graph) and English (right graph). The nitty-gritty is hard to read but you can see that there is a lot more going on for these bilinguals when they are using English than when they are using Spanish.

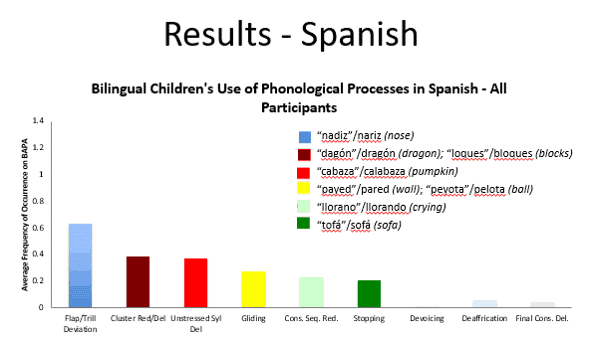

In Spanish, we see flap trill deviation, consonant cluster reduction, unstressed syllable deletion, gliding, and then less common processes.

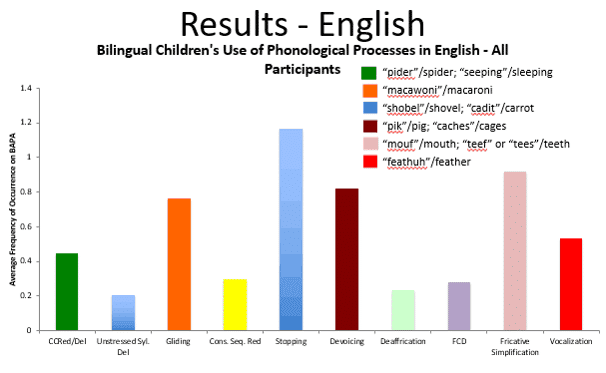

With bilingual children in English, what do we see? A lot more going on right? And don’t forget that these are children who have typical development.

Comparing Spanish and English

Looking at them side by side, red is bilingual in English, and blue represents Monolingual English speakers. We see that bilingual speakers are using several processes more than their English only counterparts. So why is that? When a speaker of another language does not have the sound or the process in the language they are trying to speak, they borrow the most similar sound or process from their first language and use it in their new language. For example, stopping was the most frequent process. Spanish does not have the voiced or unvoiced TH. Saying THE might come out as DA or saying WITH might be produced as WIT. The sounds are “stopped” because they have the T and D sound in Spanish, which is the most similar, but not the voiced or unvoiced TH.

Bilingual children have separate but interacting systems. What this means is that they will correctly use the phonological processes that are shared by the two languages and borrow sounds and processes from their first language. If we treat these processes as a disorder rather than a difference, we are going to end up with a large number of children on our caseload who shouldn’t be there. Secondly, we will be focusing on goals that the child does not need to address and we are not likely to experience success.

How Phonology in Bilingualism Contributes to Over Identification: A Case Study

If you want more information on the over identification of bilingual speech students and need continuing education credits to help you serve bilingual students, this online course presents a rare comparison of Monolinguals in English to Bilinguals in English. It will help you figure out what to focus on to improve speech and move children off your caseload.

Studies of Phonological Skills in Bilingual Children