We the (Immigrant) People

“It’s ‘we the people’, Má,” I said. “Cai Constitution bắt đầu với/the Constitution begins with ‘we the people.” Our naturalization appointment was coming up soon, and I was helping my má study. It was 1986, and I was in first grade. In class that year, I learned how to spell “like” on the spelling test. At home, I also learned with my immigrant parents about the three branches of government, freedom of religion and the number of U.S. Senators—it’s 100, by the way. At the age of six, I was already completing school registration forms for my younger sister Kim and interpreting for my father with store personnel when he had a heated comment.

Refugee Refuge

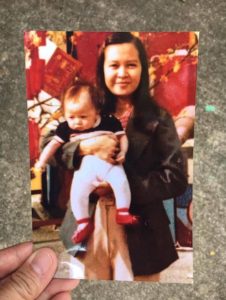

Fast forward 34 years, and I look back on my experiences as the child of immigrants. Má and Bá escaped Vietnam as boat refugees in the fall of 1978. My father, a navel boat captain for South Vietnam, navigated my mother and 54 other people in a wooden fishing boat across the South China Sea. After 11 days on the ocean, they arrived at Hong Kong’s harbor, and I was born the following morning at 3am at Tsan Yuk hospital. I assume I was one of the youngest Vietnamese refugees. After one year in Sham Shui Po, a refugee camp on the Kowloon side of Hong Kong, my parents immigrated to the United States.

Fast forward 34 years, and I look back on my experiences as the child of immigrants. Má and Bá escaped Vietnam as boat refugees in the fall of 1978. My father, a navel boat captain for South Vietnam, navigated my mother and 54 other people in a wooden fishing boat across the South China Sea. After 11 days on the ocean, they arrived at Hong Kong’s harbor, and I was born the following morning at 3am at Tsan Yuk hospital. I assume I was one of the youngest Vietnamese refugees. After one year in Sham Shui Po, a refugee camp on the Kowloon side of Hong Kong, my parents immigrated to the United States.

Sacrifices and Dreams

In recent years, my heart and brain continually revisit thoughts of my family’s sacrifices. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, approximately 200,000 to 400,000 Vietnamese refugees died on their attempted journey. We made it. My parents monumental acts have bestowed me the luxury of sitting in a lovely, well sunlit room this morning awaiting a Vietnamese family needing an evaluation for their two-year-old daughter. My favorite poet, Rupi Kaur, writes this 7-word poem:

My mother sacrificed her dreams

So I could dream

Stories Lived

This narrative is obviously significant in my life. Living the life as an immigrant or child of immigrants surely shapes the pillars of day-to-day existence. As I share my story, fellow SLPs and attendees at presentations have also echoed the same aching and heartfelt feelings. As a member of the Bilinguistics team supporting the diverse needs of children and their families, I am privy to stories similar to my own tale. As I use my brain as a speech-language pathologist to ask questions about speech sound production, receptive and expressive language or fluency, I am also listening. I hear a father quietly sharing his 7-day walking journey to find a better life. I hear an SLP-to-be getting her words out through her tears to tell me that she was also the interpreter for her parents as a little girl. “I hated doing it back then. Now, I’m so glad I was able to help them.” I see a mother providing services as a nail technician. Upon completion of the task, she turns to me, puts her teary face in her hands and tells me she is so lonely in the small rural town she lives in and doesn’t know how to help her teenage daughter adjust to America. Oh, here’s to the stories lived.

Immigrant Sentiments

The word immigrant is often used in our media with various connotations. The words English Language Learner add an additional layer of consideration for our evaluations and speech-language therapy. On this Thursday, I want us to remember that there are valuable and meaningful narratives behind these words. I can only speak my own truths, and my status as an immigrant fuels the following sentiments:

I will work hard each day because my parents earned this for me.

I will be a support system for families navigating a bi-cultural world.

I will honor the efforts of the children supporting their parents as interpreters and translators.

I will acknowledge that each tale is unique and personalized.

I will stand up and advocate for these significant narratives and valuable humans.

My parents sacrificed their lives to give my siblings and me a home in the United States. They risked, and they rallied. What began as quiet whisperings became a reality. The reality brought opportunities. It also brought significant hardship. Their engineering and teaching degrees were rubbish as they attempted to master consonant blends, final consonants, multi-syllabic words and irregular verbs. Children had to be fed. So, minimum wage labor jobs provided a consistent paycheck for our mobile home. There was no complaining, and there were no sick days or excuses. Work was a privilege, and we used our gift of labor.

We the Citizens

This past April, I spent time with fifth grade students at Laurel Mountain Elementary’s annual Immigration Day. The day is a culmination of students researching their family’s immigration stories, re-enacting the events at Ellis Island and eventually being sworn in by individuals from the office of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. I conclude each year’s event by sharing my family’s refugee tale and speaking to the value of each person’s story. I give the scholars a two-step directive. “First, know your story. Then, let stories in. You’ll find that you will share common ground in every human interaction.”

Here’s to our honorable work supporting our diverse populations, SLPs.

Phuong shares more considerations and strategies for supporting our diverse populations in Chapter 5 of The Heartbeat of Speech-Language Pathology. This book will be available to the public on September 1, 2019. We’re offering our community the opportunity to purchase it in advance (two days left!) and receive a bonus of two graphics created by Phuong.

As a fellow SLP, minority, and culturally diverse bilingual, I appreciate you. Thank you for telling your story with such grace.

Thank you, Christina. For me, I have so many identifiers (woman of color, bilingual, immigrant) that color my world on a day-to-day basis. It’s taken 40 years, but I am realizing the power in my narrative. Thank you for your words–I find solace in my fellow humans who can relate. SLP on! Take care, Phuong.

This is a wonderful article. I enjoyed reading your narrative and was impressed at how you are a strong advocate for immigrants. It is important for people to hear these stories and realize the hardships people faced and the dreams they gave up for the next generation. Thank you for spreading awareness.

Thank you, Roshni. I agree with you–hearing people’s stories is valuable. The immigrant story, each one unique and meaningful, is surely a tale to tell. Love to Millard Public Schools. I love that the district has “Be Kind” on the front page of the district’s website :). Take care, Phuong.

Thanks so much for sharing your story. Your words fill me with compassion, kindness and understanding. As an SLP who isn’t an immigrant, I’m so grateful that I can read about your experiences to better serve the families I work with.

Oh, Laura. Thank you for your words. I am overjoyed that Bilinguistics is witness to the meaningful work you do. Our team, our clients, our students and our families are so much better for it.