Evaluating bilingual children is difficult enough as it is. Sometimes the process is made worse when we work for what we believe to be a proper evaluation and we are denied access to interpreters, bilingual personnel, and are asked to come to a conclusion without any home-language information.

Why does this happen?

Administrators are under a lot of pressure to reduce costs and make processes more efficient. There is also a misunderstanding that evaluating bilingual children is actually more costly. The truth is that an incorrect evaluation puts another child on our caseload and adds to the already rampant over-identification of minority populations. The cost of 1 child in special education for one year is reported to be $5000. No, it is worth the time and expense to get the diagnosis correct.

This question came to us and the response is worth sharing.

Do you have a “cheat sheet” of some kind pointing monolingual SLPs to what the law states (and maybe ASHA) concerning best practice when evaluating bilingual children? I still get referrals for bilingual children whose placement (or lack of placement) in sped for speech-language services is due to incomplete evaluations.

I love this statement in one of the Bilinguistics resource documents:

“The message is clear. Speech and language testing needs to be cumulative (all languages) and not comparative (one language against the other).”

IDEA and ASHA both support evaluating bilingual children in a CUMULATIVE manner.

IDEA says…

Each public agency must ensure that assessments and other evaluation materials used to assess a child under Part 300 are provided and administered in the child’s native language or other mode of communication and in the form most likely to yield accurate information on what the child knows and can do academically, developmentally, and functionally, unless it is clearly not feasible to provide or administer.

[34 CFR 300.304(c)(1)(ii)] [20 U.S.C. 1414(b)(3)(A)(ii)]

A child must not be determined to be a child with a disability under Part B:

- If the determinant factor for that determination is:

- Lack of appropriate instruction in reading, including the essential components of reading instruction (as defined in section 1208(3) of the ESEA2);

- Lack of appropriate instruction in math; or

- Limited English proficiency; and

- If the child does not otherwise meet the eligibility criteria under 34 CFR 300.8(a).

[34 CFR 300.306(b)] [20 U.S.C. 1414(b)(5)]

ASHA says…

Identifying a communication disorder in a bilingual individual requires careful consideration of the multitude of factors that influence communication skills. True communication disorders will be evident in all languages used by an individual; however, a skilled clinician will appropriately account for the process of language development, language loss, the impact of language dominance fluctuation, and the influence of dual language acquisition and use when differentiating between a disorder and a difference. Language dominance may fluctuate across a patient’s/client’s lifespan based on use and input and language history (Kohnert, 2012). An individual may be fluent in conversational communication (BICS), yet continue to have difficulties with communication needs in an academic arena (CALP). Observing an individual’s language skills in both areas is essential to develop a comprehensive understanding of his/her linguistic abilities.

Here is the ASHA position paper referring to what you were talking about. A bit arcane in the language but still their stance.

Clinical Management of Communicatively Handicapped Minority Language Populations

What is truly needed when evaluating bilingual children?

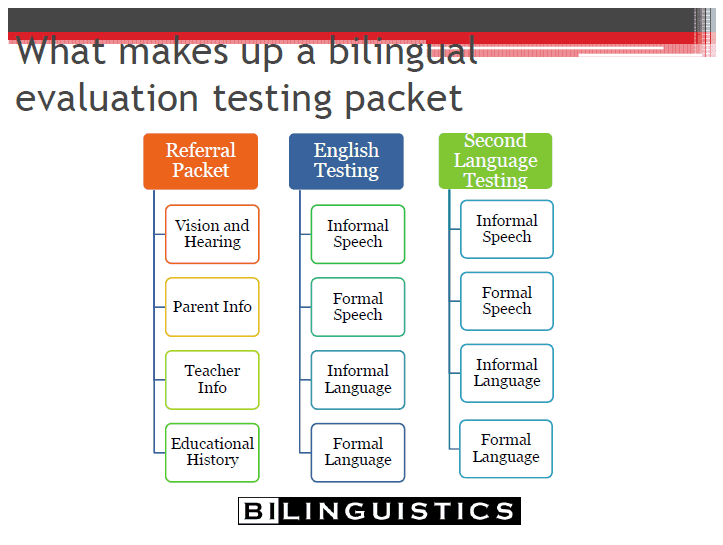

When you think about a evaluating bilingual children you have to remember that your job is 80% the same and you already know how to do most of it. Looking at the image, we see that a bilingual eval is exactly like a monolingual eval, with 4 more components. Even if you are monolingual, you can carry on in a normal manner. If you get results that are below typical, it is time to call in some bilingual support.

A big thanks to Ana Paula G. M. for her thought provoking question.

Great post, Scott. This information is so needed in the field and your comment about the expense of not doing it right in the first place is so true.

Thank you for your reference to the law as well as ASHA’s position. I would like more clarification on your position on testing NOT being comparative. Do you mean one approach vs. the other? We absolutely need to consider ALL languages (cumulative) but we also should indicate the degree to which each language is developed/present (comparative approach).

You are absolutely right that we need to think about all languages being cumulative. Let me share a research study and what this looks like on our testing.

Typical children were interviewed in Spanish about what their favorite foods are. Tacos, sopa, you can imagine the responses. The SAME-TYPICALLY developing children were interviewed at a different time in English. What do you think they said? Hotdogs, Pizza. Do you have a different favorite food just because you are speaking Mandarin? How can this be?

The answer is that language heavily influences the content. This study’s result matches what we see when a bilingual child is only tested in one language. They may appear to have less language. If we added all of their responses together from both languages (typically developing), they would like a lot more like their monolingual peers.

So know that we are saying CUMULATIVE (conceptual) not ADDITION responses. So if a child is naming animals than dog/cat/horse/chicken = 4. If a bilingual child is naming animals then dog/cat/gato/horse/gallina still = 4 (“gato” means “cat” in Spanish so that counts for one CONCEPT).

To your last point: “we also should indicate the degree to which each language is developed/present.” Yes, but all together that adds up to 100%. If a child speaks 50/50 Spanish/English or 90/10 Spanish/English it doesn’t matter. We are just checking to make sure that the concept (e.g. past tense, vocabulary) is present.

Age of acquisition and language specific concepts makes this more complex, but this is the general idea. Great thinking on your part!

Thank you for this re-clarification.

I have a question regarding development of L1 vs. L2. A student shows below average skills on the informal language assessment for L2, but approximating average, on the criterion score. Informal (deep screening) in L1, shows underdeveloped structures, lack of understanding, preference for L2 in responses, and more language skills (conceptual and structural) present in the L2 profile. The L1 screening is considered a fail .

However, it is evident that follow-up with formal testing in L1 would result in poor performance and likely discontinued subtests due to inability to perform the tasks required. Should one test L1 anyway? Also, the perennial question, should Psychoeducational Testing proceed in L2?

Hi Gilda, These are great questions. With respect to your question about whether to do formal testing in L1 when you have already established with informal testing that performance in L1 is low, I will say that for me, informal testing guides my diagnostic decisions far more than formal testing. The piece that I would add to the informal testing is a dynamic assessment on the deficits you saw in the two languages. If you see minimal improvement in a dynamic assessment, then we are likely looking at a language disorder. In this case, it sounds like formal L1 testing may not yield the information you need.

I’ll preface my response to your second questions with a disclaimer–As a speech-language pathologist, I don’t do Psychoeducational Testing BUT, I have had this conversation with many diagnosticians and Licensed Specialists in School Psychology who are bilingual. Almost all of them tell me that they use both languages in their assessments. Some parts are only completed in L2 and others only in L1 but they consider both languages. I think the thing that we need to remember is that the two environments in which the students learn their languages are different and they likely have different vocabulary in each language as a result. If we only complete testing in one language, we are likely to miss some skills.

In reference to adding dynamic assessment data to clarify more need in L2, would an additional data taken from reading scores like comprehension, decoding, etc.would be included to assure consistent (fidelity of language 2,etc.) Speech and language carry over skills in accessing the general educ. Setting? And great questions and great feed back.

Hi Roy,

Thank you for your message. Two points about your comment to start: 1) it is clear through your question that you are aligning your work with the ultimate end goal – that a child is successful in the classroom. 2) You don’t see communication as operating in a vacuum. The work we do pulls on strings in every area of a child’s life.

So my answer to you is twofold, we want to include academic performance information if we have access to it because it really helps us see the whole child and helps readers (of a report) understand WHY we are doing what we are doing in speech therapy or WHY we are making a diagnostic decision. However, we need to include an informal portion in or evaluation to clearly diagnose a problem and clearly choose goals and level of support for each goal.

As we speak, we are wrestling with ideas about how to build an online course to easily show how this is done. I think the field has a bad relationship with “dynamic assessment” because of the arduous process we were taught in grade school. It can be very fast and easy and produce a ton of information. Here is what it looks like:

You give a formal test.

A child botches something.

You dig deeper.

Let’s do a speech and language example:

Speech – can’t say /s/ at word level

you grab any book, highlight every /s/ on the page.

Try the sentence level – nope

Try the phrase level – nope

Try the word level – nope

Try clusters – nope

Try initial (nope) medial (yep) final (yep)

Try isolation – nope

Try between vowels – yep

Child will produce /s/ in isolation and in the initial position with 80% accuracy after being given an example. Then a goal for clusters

Language:

Child doesn’t describe anything, use adjectives, etc.

You have the child name as many colors as he can (5 responses)

Then sizes (no responses)

numbers (3 responses)

Then have him name as many animals as he can (7 responses)

Flip it around to receptive

child identifies 12 colors

2/3 sizes

12 numbers

16 animals

Now we have our pool. Choose from any of the adjective and any of the nouns and see if he can put them together

Child will describe an object with noun+adjective two-word phrases in 8/10 opportunities and with moderate cueing.

Great post! I have a question regarding a 6th grader who speaks both English and Spanish. With parents, she speaks both languages although spanish is probably more prevalent. She has been in an english speaking school since Kinder and I know CALP typically takes 5-7 years to develop. She would technically be on year 7 of english exposure in an academic setting. All tests that look at her Spanish skills have fallen in the same level (2 of 4) for years now. She also has a specific learning disability and is in a mild-moderate special day class. Would this be a student where I would need to test in both Spanish and English?

Yes, if Spanish is the language of the home and English is the language of the school, I would still test in both to get the full picture of her language skills.

Thank you for this! Just to piggyback off the last comment: looking at that same child who has been in school since Kindergarten and is now in 6th grade, let’s say her dominant language is clearly English now, but she still has exposure to Spanish at home, but she does not use it much. Would we ever work on goals that are just found in the English language since she has been hearing English instruction such as learning proper grammar structures in English (I.e., irregular plurals, ‘th’ sound, etc)? I think ‘no’ (for too many reasons to list here) but I have been getting this question from many of the monolingual SLPs I work with and so I began to wonder more myself. Thank you for your response.

Hi Karen,

Excellent point and the answer is: it depends on the situation. I will give some examples each way here but more often than not, you are correct in thinking that we do not include those goals. Here is some justification:

We dismiss children who are within the range of typical, not when they are superstars. Think of our qualification spectrum. Let’s say that children who have a Standard Score of 80 don’t qualify. Our job as SLPs is just to push them across that line. We turn the 76s and 77s into 81s. We don’t turn them into 90s or 100s. Many children have difficulty with irregular plurals, synonyms/antonyms, idioms, etc.

Point two is that second language acquisition makes these this difficult and we work with special education issues and not second language issues.

Finally, if there is a debate about a child – evaluate them! This means ahead of the timeline probably. But children are often DNQs (do-not-qualify) when they still have some errors present.

Times when we work on English things do occur.

1. When the “thing” is an artifact of both languages. For example, if both languages have past tense, that is a good goal (not irregular necessarily). Chinese for example, does not have past tense. They mark past with other words – I eat yesterday, I eat today, I eat tomorrow.

2. Hire English artic sounds – R-S-L. I have a ton of 3-5th graders who speak Spanish and English. There R-S-Ls are fine in both languages. Then some, have these difficulties in English. If they have been exposed to English for more than 5-7 years (BICS-CALP) then the sounds normally come in. If not, despite being “non-native speakers” I am comfortable targeting them. Especially since Spanish has those sounds too. TH on the otherhand, not a good goal because Spanish doesn’t have that sound.

Thank you! That’s exactly what I thought 😉