I’m a bilingual SLP, but when it comes to evaluating students who speak Kenyarwanda, Pashto, Tosk, and Thai, I am just as monolingual as the 95 percent of our field who self-report themselves as monolingual. Unlike many of the SLPs I talk to about this topic, I actually get excited when one of these evaluations shows up in my in-box. Over the years, we’ve put together a solid framework for evaluating students who speak a native language other than English. Today, I want to share it with you.

Understanding the Native Language and Culture

First, you need information about the student’s native language and culture. You need to know what sounds exist in the native language along with phonotactic constraints (like, you can’t start words with s-clusters in Spanish). Second, you need information about the structure of the language—things like word order, sentence structure, noun-adjective order, how the verb system works, whether articles and gender are used, what the pronoun rules are, …and so on). And third, you need information about the cultural customs for communication (like appropriate initiation of conversation between adults and children). Now, I know this sounds like a lot. Please keep reading. We want to make this easier for you, and SLPs have used and benefitted.

“I received a copy of the Difference or Disorder text this morning. I thought, ‘…take the day off, the Bilinguistics group just saved you lots of searching and organizing time for this semester and many to come.‘”Mary Ruth Fernandez, Ph.D., CCC-SLP

If you are working with one of the 12 languages we covered in Difference or Disorder: Understanding Speech and Language Patterns in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students, we’ve already done this work for you. The four languages I mentioned above are languages we’ve been asked to cover since our book was published in November of 2014, so you’ll find those in the next edition. The languages we did cover in the book include Arabic, Czech, Farsi, French, German, Hebrew, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Russian, Spanish, and Vietnamese.

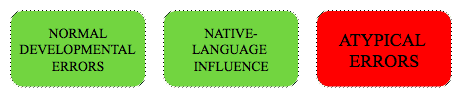

Now for a brief introduction to the framework: The hard part about evaluating students from other language backgrounds is knowing which of their errors are due to influence from their native language, and which ones are indicative of a speech or language impairment. When armed with the information we mentioned above, it is relatively easy to make those decisions and classify errors as typical developmental errors, errors that can be explained by the student’s native language, or errors that are indicative of a speech or language impairment.

Bilingual Speech Evaluation

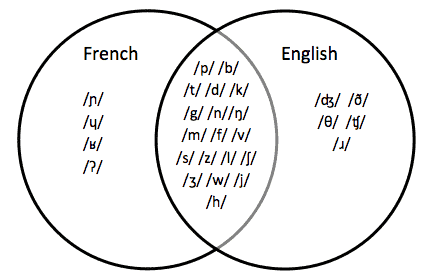

We can evaluate errors based on where we would expect influence from the student’s native language. Take a look at the Venn Diagram of French-English consonants below:

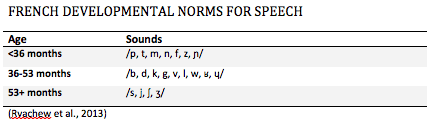

If a student from a French-speaking home is having difficulty only with /ʤ//ð//θ/ /ʧ/ and /ɹ/, we aren’t going to be concerned because those are all sounds that exist in English that do not exist in the native language. If they are struggling with sounds that do exist in their native language, and those sounds are in the range expected for the student’s age (see developmental norms chart below), then we are going to be concerned. That’s a bit of a simplified version of the process, but that is the gist of it.

Bilingual Language Evaluation

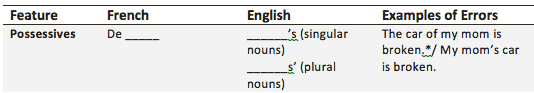

We take the same approach for language. For example, if a native French-speaking student struggles with the English possessive form but marks possessive information in French fashion, we will attribute that to native language influence and not to a language impairment.

Bilingual Interpreters

Finding an interpreter is another important piece of the puzzle for this process. To be honest, this is often the biggest challenge, and we’ve had to get pretty creative. Recently, I joined the Thai Students Association FaceBook group at a nearby university. I found someone that way initially, but when that fell through, I called my favorite Thai restaurant and found an education major who waited tables there. We’ve also gone through churches, refugee service groups, the local Chamber of Commerce, and an online association of interpreters and translators.

Once you find the interpreter, there is some training that has to be done. That’s a whole other blog post. In fact, we have blog posts on working with interpreters at The Speech Therapy Blog. Also, these documents can be downloaded from our Speech Therapy Materials Resource Library.

Informational Sheet for Interpreters

Which Students Should You Be Concerned About?

After you go through this process, you will have identified errors that your student makes and classified them as errors that are typical developmental errors, errors that are influenced by the native language, and errors that you cannot explain given their age or native language. A high frequency of such errors, combined with concerns from parents or teachers, will indicate that this is likely a student who needs the support of a speech-language pathologist.

Sounds like a lot of work, doesn’t it? And it is, but this process will empower you to get the right students on your caseload and avoid loading up your day with students who would be better served by your school’s English as a Second Language (ESL) team.

You can do this! ¡Tú lo puedes hacer! Vous pouvez le faire. Du schaffst es.