What influences sound development when a child is learning two languages? Huge question, right? Well I am happy to tell you that there are just three things that we need to take into consideration when we are trying to separate typical development from speech sound disorders when working with bilingual children. It doesn’t matter if we are using standardized or non-standardized measures when we are testing speech, we are still fundamentally looking for three pieces of information:

- Do both languages have the sounds?

- Can those sounds be used in the same places in the words?

- Are the sounds acquired at the age of the child I am testing?

Let’s take a look. We will use Spanish as our example since it is the second most spoken language in 43 of the 50 states.

1. Shared Versus Unshared Sound Comparison for Speech Sound Disorders for Bilingual Children

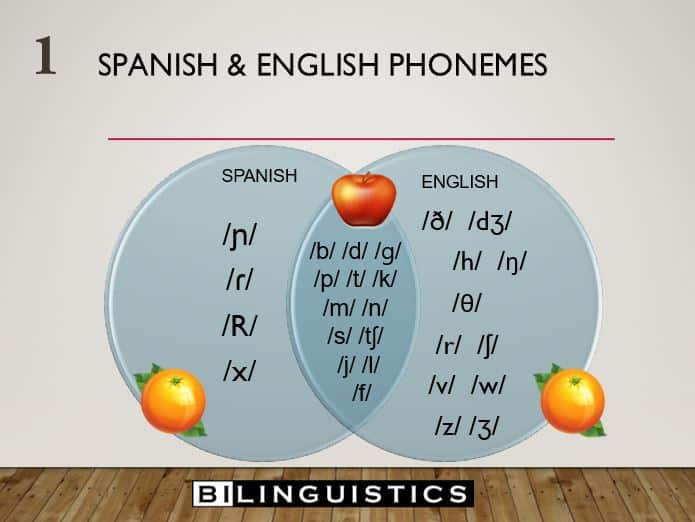

If a sound doesn’t exist in both languages, we can’t easily separate whether it is a sound error or influence from the home language. The solution? Focus on the shared sounds. Check out this Venn Diagram, the center sounds are shared so sounds like /b/ and /d/ are good targets. Sounds that only exist in English would not be.

The center of the Venn diagrams are the sounds that are shared between two languages. The sides of them are the sounds that are unique to each language. In this case, Spanish is on one side and English on the other. With these two languages, you’ll notice there are quite a number of sounds in the English language that don’t exist in Spanish. When our students or clients are making errors only on English sounds, that’s a strong indicator to us that we’re looking at an influence as opposed to a disorder.

You can make a Venn diagram like this for any language. Focus your testing on the center of the Venn.

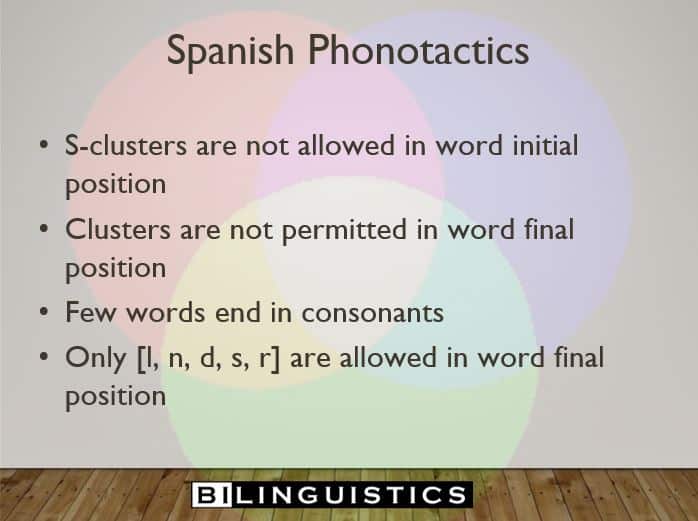

2. Phonotactics or Sound Placement

If a sound can’t be produced in a specific place in a word, we can’t easily separate whether it is a sound error or influence from the home language. Yes, Spanish has /t/, /g/, and /k/, but none of these sounds can be used in word final position. Do you want to guess how many Spanish-speaking children we find on new caseloads with Final Consonant Deletion goals? Only five consonants can be used in the final position in Spanish, and in many Asian languages there are even fewer consonants that can occur at the ends of words.

So we want to always consider what are officially called “phototactic constraints” that the language has. Check this out for Spanish.

The solution? Do artic testing first. If you are then seeing a high frequency of a phonological process, check to see which sounds can be used in each place. We might look at word lists in, say, French to see if there are clusters that are in final position. Or see if Cambodian uses /s/ at the end of words. Sometimes we have to get creative in our approach when we’re working with languages that we can’t readily access that information for. Again, most global languages are “CV languages” (consonant-vowel). Slavic and Germanic languages like English throw consonants everywhere.

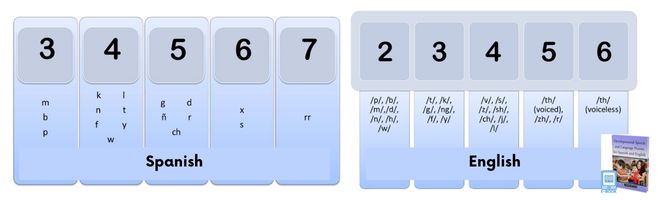

3. Age of Acquisition.

If a child is too young for the sound being produced, we can’t easily separate whether it is a sound error or influence from the home language. This one is tough because age-of-acquisition data in other languages is very hard to find. Here is Spanish up against English:

You’ll notice that they don’t line up perfectly. Early on, this is influenced by the sounds in the first few hundred words like “mama” and “dada.” Without much to go on for all the other languages we see, we are better off relying on three pieces of data:

Intelligibility: Intelligibility guidelines are thought to be the same world-over. Meaning, parents understand their three-year-olds and unfamiliar listeners understand four-year-olds.

Aging Out: Most languages acquire all their sounds by age 7ish. English actually has one of the longer spectrums and new research is even bringing that into question. So if you have a 6-year-old or older, you can feel pretty safe thinking they should have all of their sounds.

Caretaker Input: Does the child sound like other students his age and with a similar language background?

Order of Acquisition: One thing we do know is that sounds emerge in generally the same order. Stop consonants for example, come in earlier than affricates. And that tends to be true across the board.

Acquisition variation results from the ambient sounds of the child’s language. We know that variation exists, but we also know that there are some patterns that are pretty consistent across languages. So think clinically about these four aspects of age.