Can a child demonstrate a speech impairment in one language but not the other? My immediate response to this is, “No.” That said, let me tell you about a student I tested last week. Meet Miguel. Miguel is a 7-year, 3-month-old child whose native language is Spanish. He spoke only Spanish until he started school at age 3 and it continues to be the language he hears and uses most of the time. Since starting school, Miguel has received academic instruction in English with some Spanish support, and the family has continued to use Spanish in the home. His mother reported that Miguel speaks Spanish more often than English. Based on a detailed language history, I estimated that he uses Spanish 60% of the time and English 40% of the time.

Testing Both Languages for Speech Impairment

Formal and informal language testing in both languages indicated that Miguel’s language skills were within normal limits in both languages. I should note here that when a student’s language skills fall within normal limits in one language but not the other, it indicates normal language skills with low proficiency in the other language. While it is also the case that one cannot have a speech impairment in one language only, it is possible for a student to have a speech impairment that impacts one language but not the other. Huh? How does that work?

Difference or Disorder?

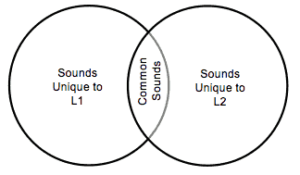

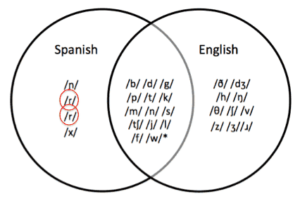

Let’s take a look at the Venn diagrams that we use throughout our book Difference or Disorder? Understanding Speech and Language Development in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. On the left side we have sounds that are unique to the first language. On the right side we have sounds that are unique to the second language. And in the middle we have sounds that are shared by both languages. When we are doing bilingual assessments, we spend most of our time focused on the shared sounds, which we expect our bilingual students to produce (depending on their age) and the sounds unique to the second language. When we only see errors on sounds unique to the second language, we can attribute those errors to the acquisition of the second language. We don’t usually spend much time focusing on the sounds that are unique to the child’s native language. Today we will spend time on the left side of our Venn diagram.

Here are Miguel’s standard scores:

- Spanish Standard Score on the BAPA: 75

- English Standard Score on the BAPA: 110

This is a big difference. But when we take a closer look, it really makes sense. Miguel struggled with sounds that exist in Spanish that do not exist in English. In particular, the trilled and flap /r/ of Spanish and any cluster with the flap /r/. The English /r/ is produced very differently than the Spanish /r/ and this student did not have any difficulty with the English rhotic /r/. So, going back to our Venn diagram for Spanish, take a look at where Miguel’s errors fell.

Here are his errors in Spanish: (not written in IPA)

- dagon/dragon

- libo/libro

- lloando/llorano

- paded/pared

- thana/rana

- dopa/ropa

- figerador/refrigerador

He also made errors on one sound in English:

- mouf/mouth

- teef/teeth

- toofbrush/toothbrush

Miguel made the same errors in connected speech that he made in single words. The next thing I looked at was stimulability. In other words, can he make these sounds if I help him. I used visual and verbal cues to teach the production of the sounds. Here is how Miguel did with extra support:

- flap r 2/8

- trilled r 1/5

- flap /r/ clusters 4/12

- unvoiced th (English) 4/7

Stimulability was low for the Spanish sounds but he did make improvement. For the unvoiced “th” of English, stimulabiity was better. He was able to produce it in 4 out of 7 attempts and then he used it spontaneously in connected speech. Such rapid improvement on the English sound, suggests a difference rather than a disorder. His low stimulability for the sounds of his native language suggests an impairment.

So, how did I answer the question, “Can a student have a speech impairment in one language only?”

I still said, “No,” but a student can have a speech impairment that impacts only one language. Here is how I talked about Miguel’s speech impairment in his report.

Miguel demonstrated articulation skills that were impaired and impacted his Spanish speech production. Miguel achieved a standard score of 75 in Spanish and 110 in English on the BAPA. It is not typical for a speech impairment to impact only one language, however, in Miguel’s case, the sounds he struggled to produce were sounds that exist in Spanish and not in English. He demonstrated errors with the trilled /r/ of Spanish, the flap /r/ of Spanish, and clusters that included the flap /r/. Stimulability with visual cues and models was low. He produced the flap /r/ in 2 of 8 opportunities, the trilled /r/ in 1 of 5 opportunities, and flap /r/ clusters in 4 of 12 opportunities. Intelligibility in connected speech in Spanish was 95%. Children Miguel’s age are typically fully intelligible in connected speech. In English, Miguel demonstrated difficulty with the unvoiced /th/ sound, which is a sound that does not exist in Spanish. This is a common error for children from a Spanish-speaking background who are acquiring English as their second language. Stimulability for the production of the unvoiced /th/ was good. He produced it correctly in 4 of 7 opportunities when provided with a model and a visual cue. Miguel was fully intelligible in English.

The next obvious question is, “Does he qualify for speech services in the schools?” We’ll save that one for another blog post. We would love to hear about your fascinating case studies too!

I have tested children in both Spanish and English whose Spanish was a lot harder to understand in connected speech. In English, there phonemes were a lot clearer as well as in connected speech.

So have I, Carol. Some of the bilingual children I see prefer to speak English if they have difficulties with articulation (especially those who have syllable deletion as a phonological process). I find that choosing therapy targets is difficult in these instances.

Have you posted the answer to the eligibility question on this blog yet? If so can you lead me to it? Thank you

Hi Gwen,

I have not yet posted the answer to the eligibility question but I’ll share with you the specifics for the student I talked about in the blog. He did not have an educational need for speech therapy. He receives all school instruction in English, and his English was not impacted by his speech impairment. His parents are fully bilingual and can communicate with him in both languages. They decided to enroll him in private speech therapy to address his production of the /r/s of Spanish. I know that the issue is not always that black and white. I’ll dive into it further in a blog post soon. We have a few other blogs coming out before that one though. Thanks for subscribing to our blog. We love the community we have here, and we love hearing stories from others in the field! Best, Ellen Kester

I have found an opposite problem..several of my bilingual students have perfect /r/ productions in Spanish and yet substitute w/r or distort vocalic/consonantal /r/ in English…

Any suggestions

Yes, we find the errors on /r/ go back and forth between Spanish and English. Spanish and English are lucky in that most of the sounds “phonemes” in both languages are the same. An “s” in English is an “s” in Spanish. However, this is not true across all languages and is not true across all sounds. We tend to think of the /r/ in this circumstance as being the same sounds, just used in different languages. However, they are very different and develop independently. A child can gain /r/ in one language more quickly because of how much they use it or how well it relates to their sound system.

/r/ in Spanish is closer to /d/. You could say that it is a /d/ with the tip of the tongue mobile (able to tap the interior space above the upper teeth or move rapidly.

/r/ in English is static. The base is held in place, typically with the middle sides of the tongue touching the roof of the mouth. Errors on /r/ are typically deviations from this position (sides of tongue go down and you get /l/) or additional movements (lips go out and you get /w/). Generally speaking here because of the huge variety of /r/ use in English. So your intuition is correct. We have to treat them separately.

The Spanish /r/ is quite different from the English versions.

In the past, I worked with a young adult in both the US and in Russia, his homeland, who, after multiple palate surgeries through childhood and into his adult years, was finally excellently fitted with an obturator. His English was, for several years, more intelligible than his native Russian. I was aware of the greater number of pressure consonants in Russian, but was somewhat surprised when he shared another reason. He stated that he was more relaxed and more verbal in English because he had never been teased by speakers of English. Additionally, he was not teased by Russian speakers when using English. This insightful gentleman is now a successful anesthesiologist in his homeland, Russia. He continues to use an obturator and speaks Russian confidently.

Thank you for sharing. That is really insightful. It is amazing when bilingualism causes different self or external perceptions. I remember in grad school foreign students came over from the the math and science departments to work on speech issues There was a Central African student who was moderately disfluent. When asked if he stuttered in his native language he said he did but he didn’t think it wasn’t considered different or a problem. Only in English was it considered different or to cause difficult communication!

Can a person have a language impairment that affects only one language? that they can only understand instructions or express themselves coherently in one language, and not in L2?

Hi Chana,

Would need a lot more data here but the long story short is that language disorders exist in both languages. For example, if a child can use past tense correctly in French but not English, that’s second language acquisition. Children with impairments can’t complete the task in either language. Something to watch out for that often causes misdiagnosis is when the L1 does not have an attribute that English has. For example, Korean doesn’t use pronouns, Russian doesn’t use articles… We would expect these speakers to have difficulty with these language aspects until they learn them because there is nothing to relate to in their native language.