There are 4 things that we need to know about treating and diagnosing phonological processes in children who are bilingual.

-

Phonological processes are quite possibly more important than articulation (Ohhh! the controversy!!).

-

The types of phonological processes are almost identical in both Spanish and English.

-

They are not suppressed at the same ages in English and Spanish.

-

There is one process that causes us the most problems with diagnostics (wicked, wicked FCD!)

This topic is best absorbed visually so let’s take a look. We released a beautiful and inexpensive e-book which is extremely helpful if you work with the little guys. Click on the book image to check it out.

Número 1: Phonological Processes are REALLY Important

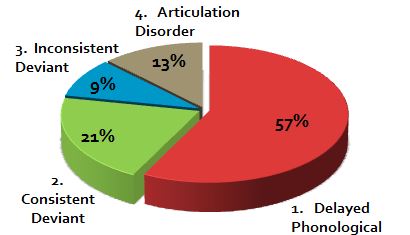

Check out this data from Broomfield & Dodd, 2004. A survey of students with low intelligibility showed that only 13% of the students presented with articulation errors. Added to this is anecdotal information from bilingual SLPs that we tend to spend a lot of time on the phonology side of the house. This could be related to the CV nature of Spanish or increased word length in Spanish.

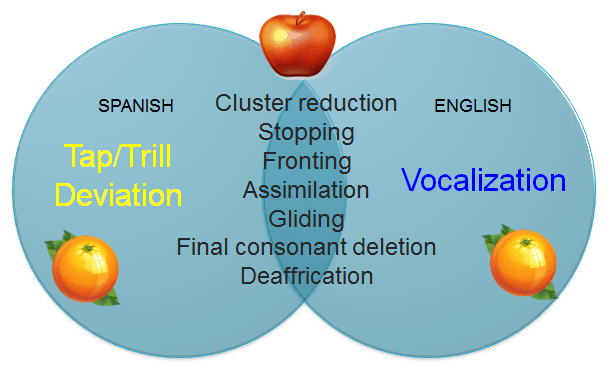

Número 2: Phonological Processes are largely shared

Easy one here. Most phonological processes are shared across many languages. For example, notice that Spanish and English have nearly all the same processes. English does not trill the /r/ so no reason to deviate it. Vocalization is when /l/ or the English final /r/ is replaced by a neutral vowel. Spanish doesn’t use the same /r/and does not have the neutral vowels leading into final /l/s that result in vocalization. Thus, it is not a phonological process seen in Spanish.

Número 3: Phonological Processes come in at different ages

So we are dealing with the same phonological processes but at what age are they suppressed? We put Shriberg’s findings (E) next to Goldstein+’s (S) to get a clearer picture.

Phonological Processes – Syllabic Patterns

| Suppressed by age: | ||||

| English (Shriberg) | Spanish (Goldstein+) | Pattern | English

Example | Spanish

Example |

| 3 | 3 (uncommon) | Initial Consonant Deletion | “at” for “cat” | “ato” for “gato” |

| 3 | 3 | Final Consonant Deletion | “ca” for “cat” | “sa” for “sal” |

| 4 | 3 | Weak Syllable Deletion | “telphone” for “telephone” | “fermo” for “enfermo” |

| 4 | 3 | Medial Consonant Deletion | “ta_o” for “taco” | “ta_o” for “taco” |

| 4 | 5 | Cluster Reduction | “fat” for “flat” | “faco” for “flaco” |

| 7 | 5 | Gliding | “bwack” for “black” | “peyo” for “pelo” |

Phonological Processes – Substitution Patterns

| Suppressed by age: | ||||

| English (Shriberg) | Spanish (Goldstein+) | Pattern | English

Example | Spanish

Example |

| 3 | 3 | Assimilation | “tato” for “taco” | “tato” for “taco” |

| 3 | 3 | Backing | “kat” for “bat” | “kate” for “bate” |

| 3 | 5 | Stopping | “bat” for “fat” | “capé” for “café” |

| 4 | 3 | Fronting | “bat” for “kat” | “bota” for “boca” |

| 7 | 5 | Liquid Simplification | “wake” for “lake” | “peyo” for “pelo” |

| 7 | NA | Vocalization | “powah” for “power” | |

| NA | 5 | Flap/Trill Deviation | “datón” for “ratón” |

Número 4: Don’t get SNaRLeD up in Final Consonant Deletion

One of the most common misdiagnoses we see for children coming from Spanish-speaking backgrounds is a diagnosis of speech impairment for final consonant deletion (FCD). Here’s the deal. English has a ton of final consonants and Spanish does not. When a Spanish speaker tries to produce a final consonant in English that cannot occur in final position in Spanish, errors are common. Worse yet, unvoiced final consonants and clusters can’t be heard by a Spanish speaker until they develop an ear for it (Don’t = Don).

Two things to know:

1. Spanish only uses 5 final consonants: S, N, R, L, & D. The word snarled is a great way to remember this.

2. When Spanish uses a final consonant it usually carries heavy linguistic weight. It can denote an infinitive verb (/r/ comer/to eat), plurality like English (tacos), or a verb tense (estás, están). This means that when these sounds are knocked out it can drastically reduce intelligibility for language and speech reasons.

Make sure you are selecting the right goals or you will be spinning your therapeutic wheels.

Research abounds on communication development. We just need a way to see how it applies to diverse young children and children in the classroom. Then we can confidently make decisions, respond to teacher concerns, and alleviate parent worries. Speaking from experience, the diversity that once made my job difficult is now the most exciting part of what I do. The world is delivered to me each day in the form of languages, songs, culture, and diversity.

We created a graphically illustrated e-book based on the research that we have gathered for our job, references for the books we have written, and materials we have developed for presentations. If you work with children, check it out!

Additional Resources for Phonological Processes:

ASHA Leader Article: Spanish Phonemic Inventory

I understand the point about FCD not being a big issue in Spanish as there are only four consonants, but the frequency of occurrence for those four consonants in conversational speech is extremely high. It impacts morphology and prepositional use of words such as “el”, “es”, “del”, “los, “las”, “al”, “en”, “con”, “por”, etc, and significantly impact overall intelligibility. I am of the position that FCD of these four consonants should be addressed if we want to increase a student’s overall speech intelligibility and develop the morphological structures where these consonants are needed.

Hi Graciela,

I completely agree with you that the five consonants allowed in word final position in Spanish have a big impact on intelligibility. They should absolutely be addressed in intervention. Most children have suppressed the use of final consonant deletion by age 3 in both English and Spanish. Now, if we see a child from a Spanish-speaking home who is learning English and exhibits FCD in English only for sounds that cannot occur in final position in Spanish, I would suspect that is due to language influence rather than a disorder.

It’s of course also extremely important to consider regional/ dialectical variations for Spanish-speaking children. For example, in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, it’s dialectically correct to delete medial “d” (ð or ð̞ in many other dialects), delete the /s/ in /s/ clusters, delete final consonants (particularly /s/ and /d/), and in some cases, delete weak syllables entirely. Some of these variations (particularly weak syllable deletion) might be considered “informal” even within the Caribbean, but are often still the norm in conversational speech. In the Northeastern U.S., Caribbean dialects of Spanish are significantly more common than Central/ South American or European dialects, so this is a particularly salient distinction here. Interestingly, I did find a study from 2005 that did not find significant differences between speech productions of children with phonological disorders who spoke Mexican Spanish vs. Puerto Rican Spanish (Goldstein, 2005); however, as I only have access to the abstract, I’m not sure exactly how errors were classified/ measured across dialects. My hypothesis would be that even if children who present with phonological disorders produce similar errors across dialects, failing to reference the dialect of each individual could lead to erroneous over-identification of phonological disorders in children whose speech is dialectically correct. While I would imagine that FCD as a result of a phonological disorder would still impact intelligibility in Caribbean Spanish, as final consonants are produced in some situations, it’d be interesting to examine whether the impact was as significant as in other dialects. I’d also be interested in whether this would impact best practice in terms of how particular aspects of instruction in morphology and literacy skills are presented based on native dialect.

Hi Casey,

Thank you for your very detailed response and for the links. The main take-away I get from looking at the many dialectical variations in any language is that we don’t want to qualify a child or focus on a goal that is just related to dialect. Sometimes “no significant differences” relates to age of acquisition of the sounds and rate of intelligibility. Intelligibility is always king and trumps sound differences.

Using FCD as an example, let’s say a child comes up with FCD after taking a standardized test. We would want to identify specific final consonants that are true of his dialect and language and check those. I often see FCD as a goal for Spanish-speakers. When you test the 5 consonants that are allowed in final position in Spanish (SNaRLeD) that are actually not impaired. Good comment!

The above ASHA Leader link goes to a “Sorry that page cannot be found” error message.

Hi Pamela,

Thanks for the heads up. Looks like ASHA rearranged a bit. I updated the link in this post.

Best Regards,

Scott