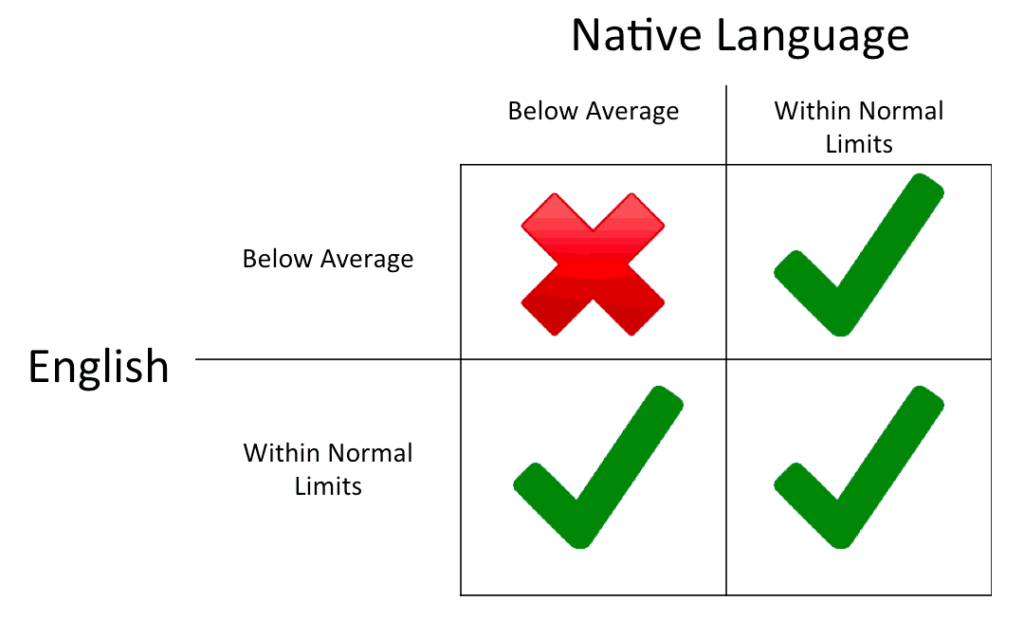

This is a question I have heard a lot lately. Is there a certain point at which it is acceptable not to test bilingual children in both languages? Take a look at the following table that comes from a workshop we do on evaluating bilinguals.

The Need to Test Bilingual Children in Both Languages

If a child falls into one of the boxes with a green check, they do not have a language impairment because they have skills in at least one language that fall within normal limits. The red X indicates a child we are concerned about because their skills are below average in both languages.

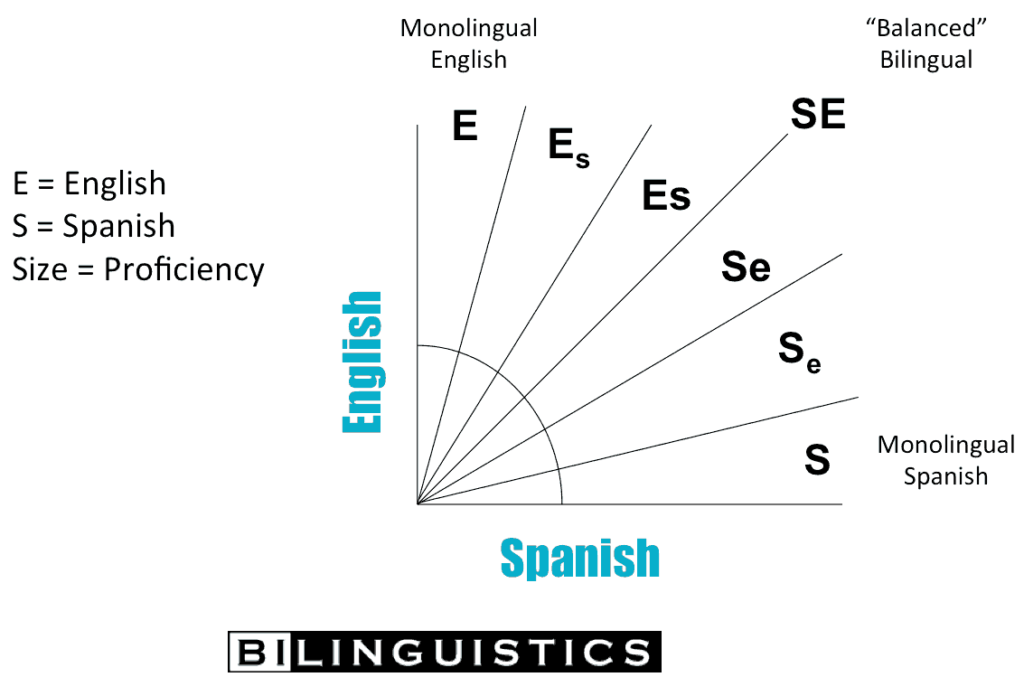

Now let’s take a look at the following chart. We have Spanish proficiency from least to greatest on the bottom (X) axis and English proficiency from least to greatest on the side (Y) axis. Along the left side are monolingual English speakers and at the bottom part of the table are monolingual Spanish speakers. In between there is a range of bilinguals with varying levels of proficiency in their two languages.

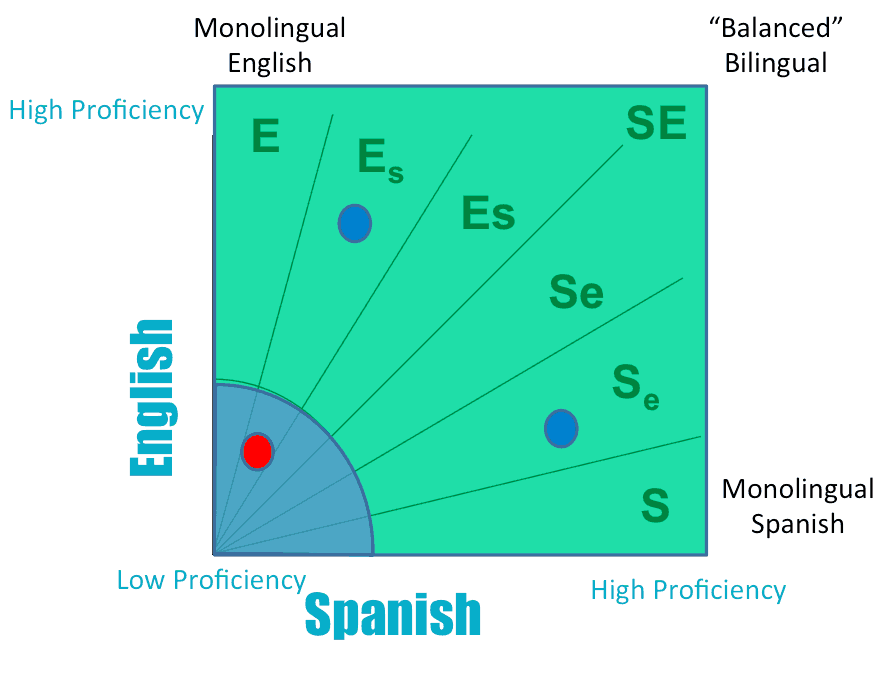

See the same chart below color coded for Language Impaired (blue area) and Typical Development (green area). If a child falls in the green section (see blue dots), they have typical language skills. If they fall in the blue section (red dot), they present with a language disorder. What I want you to notice is that both of the children who fell in the green section had BELOW AVERAGE SCORES IN ONE LANGUAGE. One of them had below average scores in English and the other had below average scores in Spanish. We wouldn’t have known their full profile if we hadn’t tested in both languages. Had we picked only one language to use in the evaluation, both of these students could have been inaccurately identified as having a language disorder.

What if I test a student in Spanish and they fall within the average range? Do I need to continue testing in both languages?

Well, you can safely say a student does not have a language impairment if they fall within normal limits in one language BUT, it is very important to be able to speak to the reason for the referral. Let’s say a student receives all academic instruction in English and they are referred for testing. You start your evaluation in Spanish and the child shows skills that are within normal limits. Then you might just do informal testing (language sampling) in English so you can evaluate the concerns of the teachers and/or parents. Teachers put a lot of time into make a referral so we really need to be able to explain what they are seeing and show them why it is not indicative of a language disorder if we decide the student will not qualify for services. Use the charts in the Difference or Disorder? book to show teachers that the errors they are concerned about are not indicative of impairment.

What if testing from the previous evaluation indicated that the child’s language proficiency in Spanish was low and English was a better indication of his language skills?

If this is the case, we need to ask the question, “Does the child still have regular exposure to Spanish?” If so, you should do informal testing in the home language so you can evaluate error patterns across both languages. If the child no longer has regular and consistent exposure to Spanish, and their earlier evaluation showed limited skills in that language, then testing in that language would not be fruitful.

While there might be a few situations in which there is not need to test a child in both languages, most evaluations for bilingual children require that we do test bilingual children in both languages.

It does take longer for us to test bilingual children in both languages, but certainly no where near the time it takes when we admit students for speech therapy services that they do not need. This is one of the primary reasons that English Language Learners are disproportionately represented in special education programs in the United States. If you need help with process, be sure to check out our online courses.

What about students who are native Spanish speakers but enroll in ESL programs with no native language support at school? Is it possible for both languages to look low because of L1 loss and L2 not yet being developed?

That is possible. If the home language stays the same, language loss is not typically a big problem but we do see that students don’t develop vocabulary related to academic vocabulary in their home language. Dynamic assessment will help you tease apart whether there is a disorder or whether their lower performances is a result of limited proficiency/exposure.

Our problem is with the many children who are ELLs and from the mid-east. We have no SLPs to test them.

When we don’t have SLPs who speak the native language we have to work with interpreters and dig up information about the child’s native language. See our Difference or Disorder book and check our blog for languages that aren’t in the book.

How do you proceed when the L1 is not a mainstream language like the Spanish example you provided? We get children coming out of early intervention for whom there are no standardized assessments in their L1 and no SLP who speaks the same language. In a public integrated preschool we encounter this evaluation dilemma all the time. How do we best proceed?

Yes, this is something we encounter a lot. We have to rely solely on informal evaluation measures. Our book Difference or Disorder? walks you through the process of how to this with a variety of languages. We also have two online courses that dive into this in detail. One is Difference or Disorder – Language and one is Difference or Disorder – Speech. Informal evaluations are also the topic for SLP Impact for the month of June.

Do schools in TX have to provide an interpreter for speech therapy if the SLP does not speak his or her language?

That’s a great question. It is best practice to do so, and some districts do provide this service. It is not required for speech therapy but it is required for evaluations.

I need suggestions on how to proceed with an early reevaluation for two nine-year-old fourth-grade twins who were found eligible for Communication Disorder in language (and one sister in articulation). Their case history forms indicate that at home the twins were/are exposed to Spanish from their mother and father (he speaks English decently) and English from their older sister and that they first attended school with English instruction at the age of five. However, dad swears up and down that they “do not speak/know Spanish” and that they communicate with mom through older sister. In addition, the most recent SLP data indicates that when asked to generate a language sample in Spanish they were hesitant/did not produce enough of a sample for analysis. Based on the pretty recent information that they were eligible for CD as well as parent/teacher report, and my own testing which places them very low, is it necessary to test them in Spanish. My overall concern is that differential diagnosis depends on assessment in both languages, but I remember that in grad school they really hammered home the point that if there’s a disorder in one language, then they clearly have a disorder. How should I proceed?

Hi Trevor,

If a student is exposed to Spanish on a consistent basis, I think it is important to explore their Spanish skills. I would explain to the parents that it is important to explore all languages the child has been consistently exposed to in order to understand their whole language system. I would also describe to the father that often children have receptive language abilities in a language even when they do not speak it often. I would use one of the wordless picture books by Mercer Mayer and tell a story to the student then ask her to retell the story, and follow it up with some story comprehension questions. That should give you a sense of their Spanish abilities and inform you as to whether formal testing is needed.

Hi!

I am a bilingual SLP and have been working with preschool bilingual Spanish kids for over 30 years. I am now retired from the school system and am doing bilingual evaluations for other school districts on an as needed basis..

I’m not sure I know how to explain this, but I think it goes like this: I, as the specialist/expert, determine dominance to the best of my ability. ( I am pretty qualified.) I then begin testing in that language and if the result is in the average range, then there is no language delay–period. In other words, any problems that exist in the other language are due to ELL or SLL (second language learning ) difficulties.

On the other hand, if the results are in the below average range, then I need to test in the second language. If both results are below average, then there is a disorder or delay. That sounds pretty simple, doesn’t it?

‘

But, in my humble opinion, there are many problems with this, the biggest of which is, money or more politely put, affordability. Most school districts, at least the ones with a large percentage of bilingual students, suffer from a lack of funds and financing bilingual testing is a big expense–especially if the child requires testing in two languages. In addition our state, (New Jersey) mandates that in order to be eligible for services, a child must score below the 10th percentile on two comprehensive tests. These tests are lengthy and require 2-4 hours total to administer. But, if you read the fine print, not only is a classroom or other functional observation acceptable, but a well-analyzed language sample will also do the trick. However, most CSTs ignore this in favor of requiring hard data such as standardized scores, percentiles, and sometimes age-equivalents, although the latter are pretty much out of favor these days. It seems to be easier for them as it closes the door they feel, on any legal action. Moreover, in our field, there are only two acceptable tests for preschool age bilingual children–and these are not rperfect since they are not truly normed for bilingual students; i.e. they are normed for English or Spanish children, despite the fact that one of them actually states that it is normed on a bilingual population.

There is also the issue of time spent on testing, which, if four tests are needed in order to hopefully establish that there is a disorder, is very time-consuming and therefore expensive! I’m sorry that this explanation is so long, but I feel that it needed saying. I don’t know why this seems to happen only to SLP’s–perhaps because we are the last hope for eligibility determination, perhaps??? Is there anybody out there who feels the same way?

Hi Leslie,

You’ve covered some ground here–I’ll try to respond to all of your points.

First, you are correct that if a child has language skills that are within normal limits in one language, we can safely say that they do not have a language impairment. I base that information on both formal and informal measures, such as language samples. I also always like to include informal tasks in the other language in hopes to speak to the referral concerns. I don’t do language dominance testing. Instead, I look at both languages. If one seems stronger, I start with that one. And yes, if they are low in both languages, that is an indication of language impairment.

You mention that it is expensive to test in both languages. It definitely takes longer but it is far less expensive than qualifying a student for services and serving them unnecessarily for a long period of time. As far as 2 tests per language, I think the use of one formal measure and one informal measure gives you far more information than two formal measures. And you are correct that there are not that many well-designed tests for us to choose from. In fact, I would argue that informal measures, such as a language sample analysis, gives you much more rich information than formal measures. When we combine formal tests with analyses of language samples and dynamic assessment to look at learning potential, we can confidently make diagnostic decisions without the need for two different formal measures in each language.

I recently tested a first-grade student. She is 6 years old and speaks English. Though mother marked “Spanish” on the home-language survey, this child speaks very limited Spanish. She is exposed to Spanish and English at home. Using the TAPS, CELF-5, SALT, extension testing, dynamic assessment, and teacher input, the child is scoring in the average to the low-average range. When the child scored slightly below average on CELF-5, the extension testing and dynamic assessment indicated that the child’s skills are typical in English. Parents do not agree their child should be exited from special education and are requesting an IE. Our local SELPA SLP recommends I do testing in Spanish. The child is performing at grade level and within average to low average in all testing, in English. I do not see the need for the child to be assessed again, let alone in Spanish. Thoughts?

Hi Scott,

It sounds like you have done a very thorough job of testing and feel very confident in your diagnostic decision. It’s always tough when not everyone is in agreement with the results of testing. You are correct that we can rule out a language impairment by showing that skills in one language are within normal limits. This is tougher when skills are in the low average range and we have parent concerns. My first question is about what specifically the parents are concerned about. If Spanish testing helps to speak to their concerns, I would certainly do it. Often, I like to look at receptive abilities in Spanish and I try to get an expressive language sample for students like this, whose home language is Spanish and who use more English than Spanish. This helps demonstrate for everyone the differences in proficiency in the two languages. It also sounds like, in this case, it would support your selection of tools and tasks.

Parent concerns are in the area of stuttering, reading, and writing. The child had dysfluencies over the summer. However, it decreased significantly as school progressed. Teacher and classroom support have no concerns. Her language sample showed no concerns regarding stuttering. With regard to reading and writing, she is at grade-level. I understand that every child can benefit from speech services, but I have to find “adverse impact” on the child’s educational progress, regardless of parent concerns. The child is not showing an educational need for services.

I totally agree with you. It doesn’t seem like there is an adverse impact on her education. If stuttering is the area of concern for parents and they are communicating with the child in Spanish at home, I would ask them to make a recording you can analyze–check out yesterday’s blog post with the stuttering calculator I use. Also let them know that if stuttering increases at some point, they can always request another evaluation. I hope that with a good conversation with the parents, you can avoid the independent evaluation. Sounds like you’ve really covered all of the bases.

My district uses parent input packets to sort whether a student needs bilingual testing or English testing, or English with an oral lang sample in the other language (Spanish, Mandarin, etc) before English is tested. If a child hears the other language sometimes or most of the time, but cannot speak the language and only knows some words/phrases, and is in a monolingual English classroom, would an oral lang sample be the first thing to look at in order to check proficiency? How much of the other language (understands common phrases, hears it sometimes, speaks it sometimes..) requires a bilingual evaluation. We are trying to figure out how to best use the limited number of bilingual slp’s but many times monolingual slp’s get apprehensive when they see a higher receptive ability. We also see that when these student’s who may understand a bit more than what they can express in the other language are sampled, their other language is often time negligible, requiring English testing only with consideration of bilingual phenomena. If you have any other resources or research I can refer to I would be happy to go read more on this. Thank you

Hi Carolina, This is always a challenging issue because of the limited number of bilingual SLPs. If students are tested in English and their performance is within the average range, we can rule out a language impairment that way. The problem is that if they are below average in English, we have to know what their skills look like in their native language in order to make a diagnostic decision. I would start with a language sample to get a sense of whether full testing needed to be done. Here are some resources on this topic:

Peña, E. D., Bedore, L. M., & Kester, E. S. (2016). Assessment of language impairment in bilingual children using semantic tasks: Two languages classify better than one. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 51(2), 192-202.

ASHA on Bilingual Service Delivery

Bilingual assessment practices: challenges faced by speech-language pathologists working with a predominantly bilingual population

Is it a state or federal law that we need to test a bilingual child in both languages?

Hi Leticia,

It is federal law. ASHA summarizes it nicely here.

what do you do if you have to conduct a bilingual eval in Spanish in English on a 6 year old sequential bilingual who was Spanish speaking for the first 4 years of their life but then once they got to the school, the child only speaks English? What if the child refuses to respond to you in spanish even though they understand it completely? How are you suppose to provide L1 information?

Hi Loevy,

This is a great question and a situation that we encounter frequently. First, for a 6-year-old you could use a bilingual tool like the PLS-5-Spanish that allows you to administer items in both English and Spanish. The child can answer in either language. This gives you a picture of the child’s OVERALL receptive language abilities rather than their receptive language abilities in only one language.

For expressive, it gets a bit more challenging. First, in the child’s English language sample, you will want to look for patterns of Spanish influence. Even if the child is not using a lot of Spanish currently, the fact that they spoke it the first 4 years of life indicates that we should still expect to see influences from Spanish. Patterns that result from language influence are likely not indicative of a language disorder. Patterns that cannot be explained by language influence could be indicative of language disorder. Once you have established those patterns, you will want to do some dynamic assessment to look at language learning and response to teaching.

Another thing you can do to explore L1 is to see if the parent can audio record a language sample for you–either conversational or a story in the home setting if the child is using L1 there.

Good luck and keep us posted on how it goes!

I’m trying to track down an ASHA article that I thought I had saved years ago. It’s about testing bilingual students in both languages- even if they’ve passed their English proficiency. That may not mean we do thorough testing in both languages but at least sampling of each language with the use of a bilingual SLP or an SLP and interpreter. Have you seen this article? Or what are your thoughts on this?