Diagnosing speech impairment in English language learners is one of the biggest challenges speech-language pathologists face. How do you know if errors result from an influence from the child’s native language or whether they result from speech impairment?

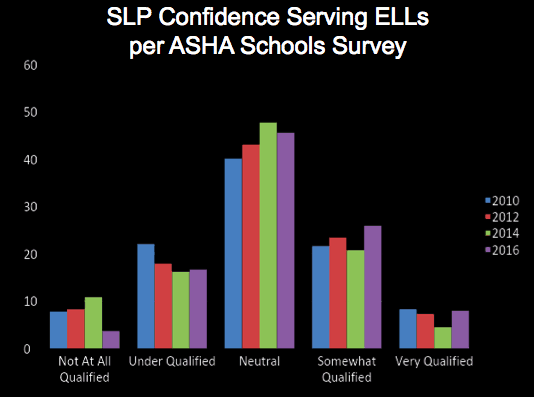

If you are like most speech-language pathologists, you don’t feel very confident identifying speech impairment in English language learners.

Fewer than 10% of speech-language pathologists rate themselves as “Very Qualified” to serve English language learners. Even when we combine the categories of “Somewhat Qualified” and “Very Qualified,” fewer than 30% of speech-language pathologists fall into those two categories combined. That leaves more than 70% of us who could use some guidance to better understand language speech development in English language learners.

We break it down into 3 simple steps

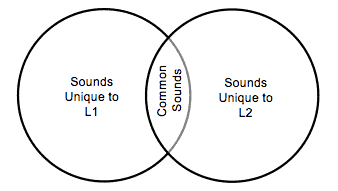

First we look at the sounds that are shared between two languages and the sounds that are unique to each language. If errors occur on the sounds in the middle of the Venn diagram, we might be concerned. If errors occur only on sounds unique to English, we attribute those errors to native language influence.

Next, we look at the phonotactic constraints. For example, if a child omits a sound at the end of a word and we know that the sound exists in both languages, we next need to determine whether the sound can occur at the end of words in the child’s native language. If it doesn’t, we can attribute the error to native language influence.

Finally, we have to consider the developmental acquisition of sounds (click here for our e-book on developmental information). If the sound is a later developing sound that typically occurs around age 6 or 7, we are not going to be concerned for a 3-year-old.

So, there you have it. 1 – 2 – 3! That was the “in a nutshell” version of understanding speech development in English language learners. If you want to dive into this in more detail, watch our course: Difference or Disorder? Speech Development in English Language Learners. Share this with your students and colleagues to help them build confidence in working with our increasingly diverse population.

So if a bi-lingual student comes to me unable to articulate “th” a sound unique to L2, does that mean that speech therapy is not warranted?

Hi Kristin,

That is likely the case. You also want to look at what the child is substituting for the “th” sound. Does it make sense given his L1? For example, do they substitute something close from their native language? You can also do a quick teaching session to see if the child can produce the sound with visual models in isolation. While we might not expect them to use it in connected speech, we want to be sure that their difficulty with that sounds does not result from structural differences or something that keeps them from making the sound at all.

Are second and third generation students that receive EL still held to the same 3 steps. Most of these kids do not speak their parents home language and never have. They hear it in the home some of the time, but many of the parents are fluent English speakers as well. Is there any research out there that addresses articulation among EL’s that do not speak a second language, but may have a second language in thier home environment.

You make a really good point. With the huge diversity of our caseloads, sometimes the “normed” group are the kids in their zip code. A.k.a. – their classmates. I often ask teachers how different the child is from his classmates. A great way to phrase it is: “Ms. Johnson, how many students do you have? 19? Great. So out of those 19, what number is she?” Typically you get that they are in the middle (not an issue). But I have had some teachers say “He is #20!” Then you have something to work with.

Yes, I hold all diverse students to these 3 steps. With children who are not impaired it is super fast. Most EL students can produce the sound just by imitating you. That’s not a disorder. If they struggle, you should do further testing. Also, don’t forget that intelligibility is the highest standard. If you student is 100% intelligible, chances are they are replacing the sounds with culturally acceptable substitutions (/d/ for /th/) and that may not warrant services.

What about a student who is a native Spanish speaker who substitutes /f/ for /th/? He is 8 is very stimuable for /th/, and in a structured task will self correct. I see one chart about that has /th/ in at 7 and the second one that lists it at 8.5 for English speakers. If the norm truly is 8.5 for English speakers, would I expect it to be later for ELL students? And do the specific substitutions effect the decision for therapy?

Hi Kristie,

the /f/ for /th/ substitution crosses a lot of boundaries. The sound charts are all bonkers and don’t match up because if you look at their data, they defined mastery differently. Some say 70,80,90%. The populations used to come up with those numbers are very different with some having a few samples and some having huge samples. So we kind of have to average but shirberg’s data is usually referred to as standard.

Stimulability – If a child can make the sound with little or no mediation, it might not be a good goal if that is the only thing they are working on. If you are in the schools, dismissal often depends on 70% mastery and always relates to academic need. Is his writing fine? Can he point to /f/ or /th/ receptively when you make the sound? It definitely doesn’t affect intelligibility.

Culture – depending on where you are at, this substitution is acceptable. Another way of saying it is, do the other children in his class/neighborhood make that substitution? Check this out. It is a study that predicts /th/ leaving the English language by 2066.

Great thinking on your part.