I have two questions related to how we treat discourse in speech therapy :

What level of discourse is the focus of our formal evaluations?

- Most prompts on all of our formal testing instruments require single word or single sentence responses.

What is a child expected to produce in the academic setting?

- Meaningful communication in long utterances and paragraphs.

Do you see the huge gap here? And how are we currently resolving this?

We focus on discourse in speech therapy for all those months between evaluations. Sometimes our therapy needs to focus on the little pieces. But if we always keep the end goal in sight – we will dramatically improve the outcomes of our therapy. Here is the BUY-IN needed to make discourse a main focus for you and then we will talk about how to easily do it.

Discourse Assessment

Discourse is the naturally occurring unit of language. Historically, models of brain and language behavior have been constructed primarily on the basis of comprehension and production of words and sentences. Within recent decades, however, linguistic analysis has expanded beyond word and sentence-level evaluation to include analysis of discourse.

Discourse measures have proven to be valuable tools for assessing preserved and impaired communicative abilities. It has been proposed that discourse tasks are more sensitive and more functional indices of communicative abilities than are traditional standardized language impairment measures.

Discourse in Speech Therapy

First, the heavy stuff:

As a clinical tool, discourse analysis has great potential for deferentially diagnosing a variety of clinical populations and making predictions about the impact of language disorders on communication in real-life situations (Bloom, 1994). (Hatch, 1992) asserts that narrative discourse is the most universal discourse genre, as all cultures have storytelling traditions. Ulatowska and colleagues have documented that personal narratives relating a “frightening experience” tend to result in dramatic and lengthy discourse in Caucasian and African-American subjects (Ulatowska & Olness, 2001).

Now, the fun stuff:

If we take our professorial bow-tie off and set our pipe down, what we are really saying is that we are looking for a way to get a child to INDEPENDENTLY combine all the small parts of language into something big and pretty. Here is a really easy template to use with any fiction or non-fiction story and get a really robust story.

Let’s start by defining ROBUST:

When I say robust, I mean that a child tells a:

- 4-part story

- In the right sequence/order

- Using cohesive elements (first, then, after, at the end)

- Answering 4 questions for each part (who, what, where, when)

This is best illustrated through the growth of language over time. You can start your kids at the beginning or the level you deem most appropriate:

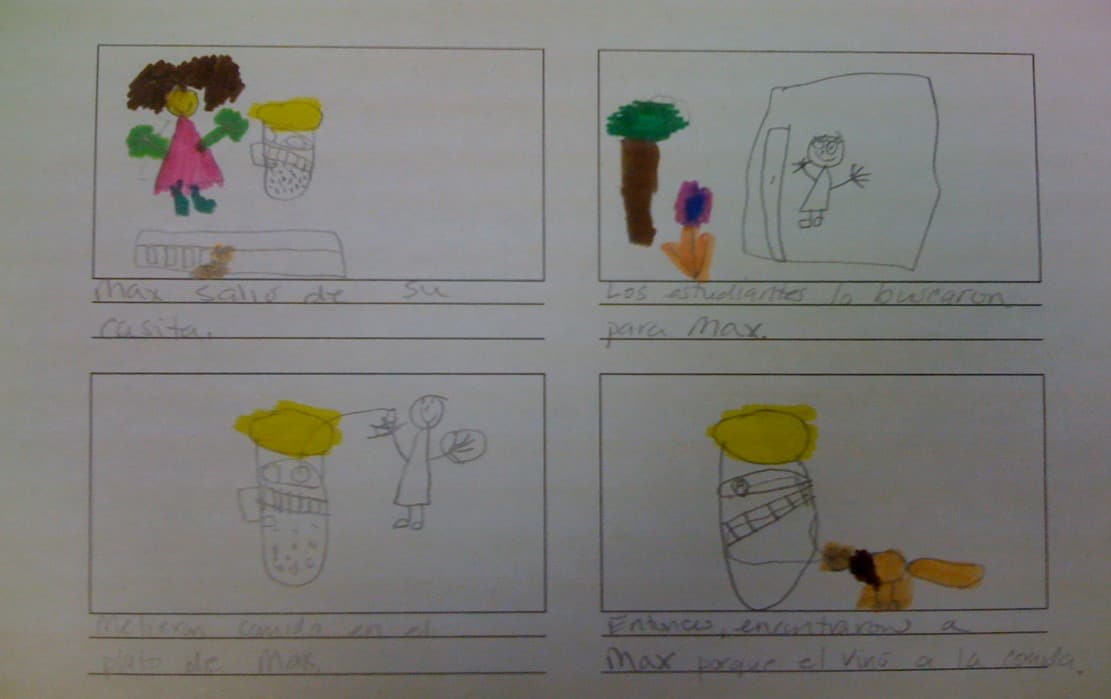

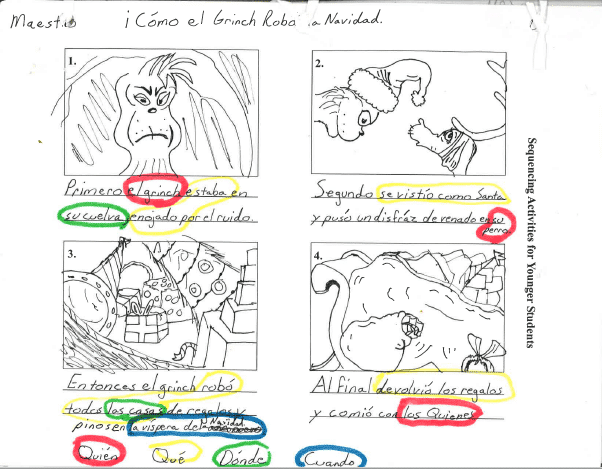

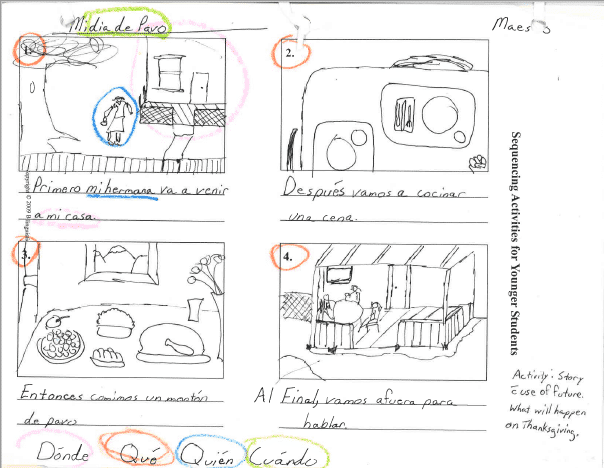

- Draw four pictures related to the story.

- Write the words FIRST – THEN – AFTER – THE END under each square.

- Write what the young child says or have them write a sentence.

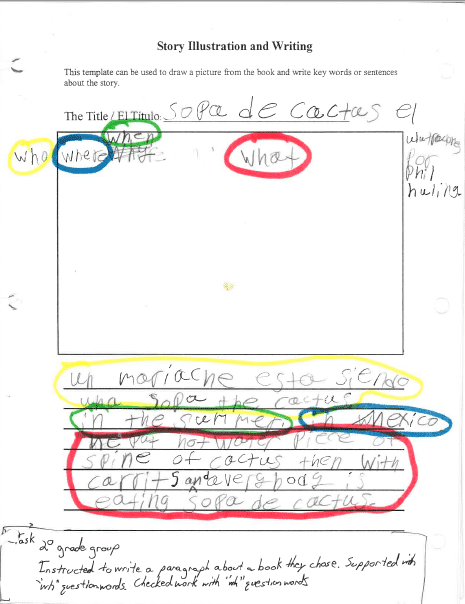

- Use colors to circle identify WHO WHAT WHEN WHERE for each quadrant.

- Ask them what they were missing if anything.

- Do this for every square.

By the end you will have a student who knows exactly what to produce and how to auto correct. Here are some finished examples from children at different levels.

WHO/WHAT/WHEN/WHERE + FIRST/SECOND/THEN/AT THE END

Non-Fiction Example: My Thanksgiving Day

1st/2nd Grade level: Incorporating WHO/WHAT/WHEN/WHERE in writing

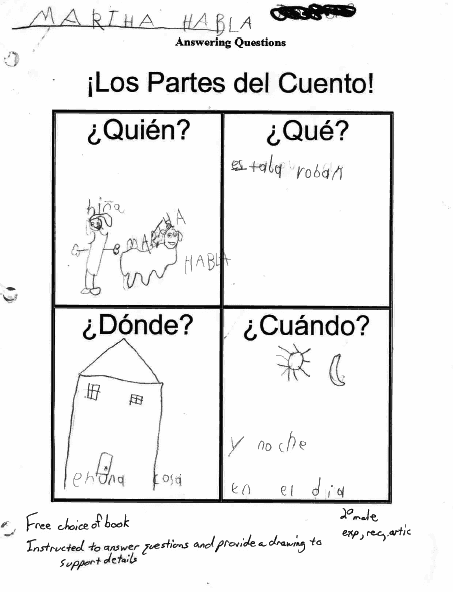

Kindergarten level: Identifying WHO/WHAT/WHEN/WHERE

References:

- Chapman, S.B., and Ultatowska, H.K. (1992). Methodology for discourse management in the treatment of aphasia. Clinics in Communication Disorders, 2, 64-81.

- Kiran, S., and Tuchtenhagen, J. (2005). Imageability effects in normal Spanish-English bilingual adults and in aphasia: Evidence from naming to definition and semantic priming tasks. Aphasiology, 19, 315-327.

- Ulatowska, H.K., and Chapman, S.B. (1994). Discourse macrostructure in aphasia. In R.L. Bloom, L.K. Obler, S.deSanti., & J.S. Ebrich (Eds.), Discourse Analyses and Applications: Studies in Adult Clinical Populations (pp. 29-46). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Unfortunately, in my experience, while longer utterances are encouraged in the early grades, by the time students are in middle school I’ve seen longer explanations/responses/observations discouraged by teachers. Why? Time constraints related to strict requirements re amount of material to be covered, class size, teacher self-unawareness, etc are some factors.

Great comment. We can get HUGE amounts of information in shorter utterances and I think that Discourse is that way to do it. Notice in the example that there are really only 4 sentences. Each sentence has the WHO WHAT WHEN WHERE of the content. Yes, middle schoolers and high schoolers are asked to be CONcise. We can facilitate this by making them more PREcise with the words they are writing or saying. Thank you for your contribution.